A number of academic studies have shown that small-cap equities – those with market caps from US$300 to US$5 billion – have historically outperformed large-cap equities on a risk-adjusted basis. What is the prevailing reason for this phenomenon?

Rolf Banz’s 1981 study was one of the first to highlight the small-cap outperformance, challenging the prevailing Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), where an asset’s return is explained by one variable – its systematic risk.

The academic consensus progressed toward introducing additional elements of risk to explain equity returns.

In their seminal paper, Professors Fama and French concluded the outperformance of small-caps over large-caps was due to an element of risk unique to small-caps (ie. investors are compensated for undertaking additional risk).

More recently JP Morgan research also noted the economic sensitivity of small-caps. The study showed that since 1990, the revenue growth rate of European small- and mid-cap stocks has been 2.2 times nominal GDP growth.

Furthermore, we don’t think this history of outperformance is the result of just one or two outsized years or biased toward a given start date, as evidenced by analysing rolling periods.

Over the last 15 years, on a rolling one-year basis, global small-caps outperformed large-caps 67 per cent of the time.

Over three- and five-year rolling periods small-caps outperformed large-caps in 83 per cent and 96 per cent of the time, respectively.

With this in mind, a small-cap allocation on its own can be rewarding, especially for investors with longer time horizons.

This small-cap performance has historically been enhanced by an active stock selection approach.

Historically, small-cap active managers have a better record of adding value than their large-cap counterparts.

Over the past 10 years, active small-cap managers have added more than 150 basis points of outperformance per year, while large-cap managers have added just over 60.

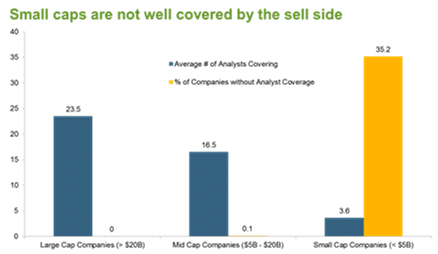

We believe this is because the market for small-caps is not as efficient as the large-cap market. Globally, the small-cap opportunity set is vast and at the same time is thinly covered by analysts. Currently, around 20 per cent of small-cap stocks in the MSCI Small Cap Index do not have any sell-side coverage, which would be unthinkable in large- or mega-cap equities.

In addition, global small-cap managers have a much larger investable universe than global large-cap managers – the MSCI World Small Cap Index has 4,265 constituents, compared with the MSCI World Index’s 1,645 constituents.

With nearly three times as many companies in the index, small-cap managers have a much wider opportunity set than their large-cap counterparts.

There are of course risks associated with small cap companies.

In general, small-cap companies have a more varied record of corporate performance than large-cap companies.

And, while they strongly outperform in growth environments, many small-cap companies face difficulties when the economy contracts.

For Australian investors, global small-caps can be an important diversifier. If an investor is overexposed to banks or resources, many global small-cap stocks will have very low correlation to these names.

The investable universe for global small-caps is currently composed of a much higher weighting of cyclical categories, such as the consumer discretionary, industrials, and information technology sectors. In many cases the revenues of these small-cap companies are less likely to be exposed to any downturn in the Australian economy.

Small-caps can be riskier than large-cap companies.

However, when you consider the return trade-off and the alpha potential active managers can offer, they remain a potentially compelling risk-adjusted proposition, particularly for Australian investors needing diversification.

Fundamental stock selection can also be important in managing the risks of investing in global small-cap companies.

Edward Rosenfeld is a portfolio manager and analyst at Lazard Asset Management.