Over the past decade, EM indexes have proliferated, making investment decisions more complicated and diminishing the effectiveness of the simple asset allocation approach to EM investing that was used in the past.

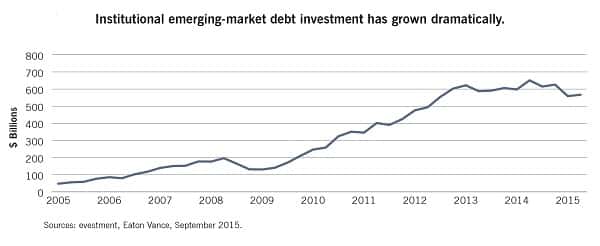

Over just the past six years there has been a global five-fold increase to US$600 billion in institutional holdings of EM debt (shown below). This has resulted in a dramatic change in the indexes that guide the asset class and a significant dispersion of asset performance across asset type and issuer.

A top-down, asset allocation approach to EM debt investing is flawed. Country risk factors are major drivers of asset performance and, unfortunately, country representation across popular indexes varies greatly.

EM debt investing is also more challenging because the opportunity set has expanded, illustrated by the growing complexity in JP Morgan EM indexes.

Investment managers view this expansion favourably because it offers a larger and more diverse opportunity set and new risk factors such as currency exposure and corporate credit.

However, it also introduces a greater level of complexity to investing in the sector.

The top-down approach to EM debt can also expose an investor to concentration risk. For example, Eaton Vance found in December 2015 that local currency Russian debt was more attractive than external debt.

Therefore, top-down asset allocation that gave equal weighting to the county’s local currency and external debt would be boosting concentration risk in a less-attractive asset class.

Instead, focusing on the ‘small things’ is a better approach for investors seeking traditional EM exposure. Disaggregating and evaluating the idiosyncratic risk factors of EM debt at a country level is an approach that can be a consistent source of alpha.

It would be hard for an analyst to gain an edge when focusing on macroeconomic ‘big things’ as the potential for adding alpha is often inversely proportional to the size of the crowd following these risk factors.

There is also limited research for off-benchmark issues when considering EM debt.

This helps make the market less efficient than for benchmark country debt.

Off-benchmark countries are typically off the front pages, and many impose heavy documentation and administrative burdens on investors.

As much as they are obstacles, they also create opportunities for investors who develop the necessary expertise and devote sufficient resources.

The ‘big things’ versus ‘small things’ contrast goes beyond the potential for alpha generation, with important implications for portfolio diversification.

In the past 10 years, EM index investing through ETFs has grown tremendously and performance of benchmark-country debt has become increasingly correlated with developed-market ‘big thing’ factors.

As a result, portfolio allocations based on EM index debt are less capable of delivering diversification with other asset classes than they have been historically.

Conversely, off-benchmark issues still have low correlations with developed-market debt.

The bottom line is that ‘big things’ are fun to talk about, but difficult to make money from consistently.

‘Small things’ are not as glamourous, but can be easier to profit from consistently.

A focus on the smaller factors can lead to the total return and diversification opportunities that are the classic hallmarks of EM debt for investors.