In particular, the logistics of a British exit are not simple, the time frame for completion is in years not months and it remains to be seen how co-operative EU officials are in facilitating a UK departure.

However, what is likely more significant now is that this outcome is likely to trigger other countries to review their options and decide whether EU membership is really worthwhile.

Ever since the global financial crisis triggered serious economic and social problems in countries such as Spain, Ireland, Portugal and, most notably, Greece, the strength and role of the EU has been questioned.

There has been a huge amount of material written on Brexit, most of which focuses on the pros and cons of remaining in the EU, and of course the impact of an exit on global markets.

But for voters in Britain, we believe the key question was: what has the EU delivered for their country, and for them as individuals?

This needed to be answered before they could look ahead towards potential future rewards.

This question is also key for any future departures and we address that for two of the three biggest eurozone members – Germany and Italy.

Germany versus Italy

There is no doubt that EU membership has been underwhelming for Italy from an economic growth and employment perspective, particularly compared with Germany.

On almost all economic and fiscal comparisons, Italy has been a laggard since joining the eurozone, while Germany has gone from strength to strength. For example:

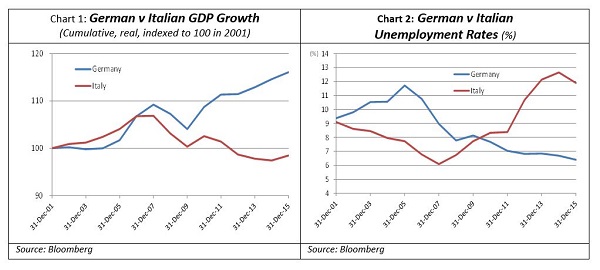

- GDP growth in Germany has far outstripped that in Italy (Chart 1) since 2002 (the start of the eurozone);

- Unemployment in Italy is nearly twice as high as unemployment in Germany (Chart 2);

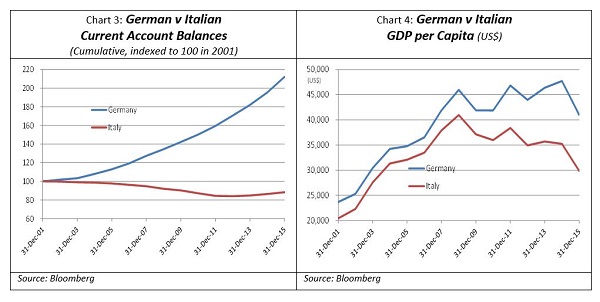

- Germany has consistently run current account surpluses (Chart 3), while GDP per capita, a broad measure of individual wealth, has diverged sharply between the two countries (Chart 4); and

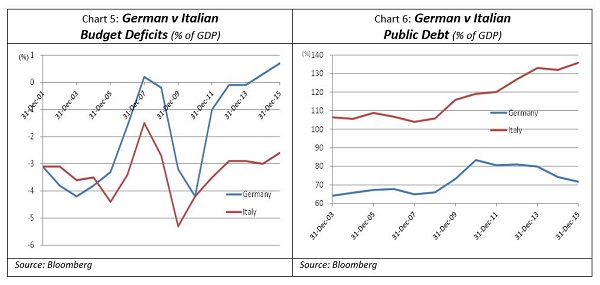

- Germany has a budget surplus (Chart 5) and a stable, manageable public debt load, while Italy continues to struggle with budget deficits with public debt at 130 per cent+ of GDP and growing (Chart 6).

Looking at these charts, it would be understandable if Italians were associating EU membership with their economic woes.

It’s easy to imagine the Italian government closely monitoring the Brexit vote and wondering whether they too should reconsider their membership.

After all, there is no doubt there is a structural flaw in the eurozone which has supported the unequal economic outcomes for countries such as Italy.

This flaw is that, unlike the United States, the UK or Australia, the eurozone is only a monetary union and not a fiscal one.

This means that, while members of the eurozone control their own spending and taxation policies, they remain inextricably linked via a single currency.

Therefore, they don’t have the benefit of independent monetary policy or a free floating national currency to help adjust and retain international competitiveness during difficult economic times, and provide a ‘brake’ in times of prosperity.

For example, in Australia, the depreciation of the Australian dollar against the US dollar during the mining slowdown has helped re-establish the competitiveness of the Australian manufacturing and service sectors.

However, eurozone members faced with competitive pressures, can only try to improve productivity, primarily through labour market reform – something that is increasingly unpopular, as strikes in countries such as France illustrate.

Nonetheless, it is too simplistic to blame the varying economic fortunes of Italy and Germany on EU membership alone.

Many of Italy’s problems predate the eurozone while equal, if not more significant contributors to that divergence are the differing history, society, and culture of each nation.

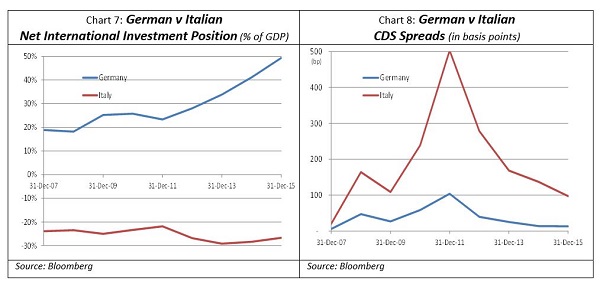

Countries such as Germany made many of the tough structural changes to their economy early on. The weaker euro means Germany has continued to benefit from very strong export dynamics (hence the substantial current account surpluses) and is a very significant beneficiary from EU membership.

This is a key reason why Germany works so hard to maintain the union – as evidenced by its efforts to keep Greece afloat and inside the tent.

Whether these efforts will be successful is yet to be seen, but there is no doubt that the simple fact of a Brexit vote – regardless of the outcome – makes it easier for other countries to decide to put their own membership to the test.

The experience of a country such as Italy since joining the eurozone makes it an obvious contender for considering an exit, and it is surely not alone.

The inevitable question is: who will be next?

Greg Goodsell is global equity strategist with 4 Dimensions Infrastructure