Inflation has only been a problem because there hasn’t been enough of it. Lack of inflation fuels fears of deflation, despite lengthy and innovative attempts by central banks to stimulate growth and push prices higher.

However, inflation is seemingly at an inflection point. The word ‘deflation’ may exit the financial lexicon over the coming months as commodity prices stabilise and global excess capacity is slowly reduced, and investors position for modestly higher rates of inflation.

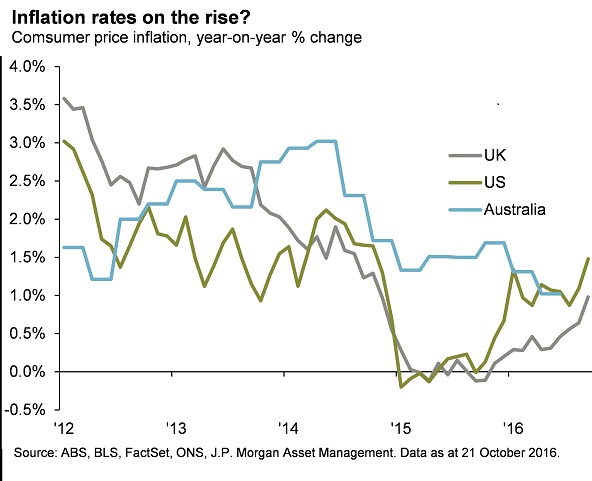

In the past week, inflation in both the UK and the US has reached the highest rates in almost two years at 1.0 per cent and 1.5 per cent year-over-year respectively.

In the US economy the rise in the price of oil over the last year is filtering through into higher energy costs, meanwhile the UK inflation rate got an additional boost from the tumbling value of the pound.

Sterling has declined by 16 per cent on a trade weighted basis since the EU referendum back in July and 22 per cent since last November. It’s worthwhile to note that an increase in inflation in these two economies can result in very different policy responses.

In the US, rising prices is a signal of a healthier economy and removes another obstacle to the Federal Reserve hiking rates later this year.

The story is very different in the UK as rising inflation is a symptom of the stress that the threat of a ‘hard brexit’ is placing on the economy.

This could result in further easing of monetary policy as the Bank of England is prepared to look past the near term rise in prices, preferring to focus on the potential drag on growth of the UK extracting itself from the European Union.

In Australia, we may not yet be at the point were we start to see inflation rise, and there are structural reasons for why inflation is low and why it can remain relatively benign – international competition in retail and low wage growth are just two examples.

We do not expect it to plunge further however, and the rate of inflation here has not skirted with deflation as it has in the UK and the US.

This week’s inflation release will be critical for the outlook on monetary policy, given that the rate of inflation has missed the bottom of the RBA’s target band for six consecutive quarters already.

The RBA’s current projection is for inflation to be 1.5 per cent year-on-year in December and then remaining between 1.5-2.5 per cent in 2017.

Only if inflation threatens to undershoot these already low projections will the RBA be spurred to cut rates again and, as a reluctant cutter, they will likely keep rates where they are into next year.

The outlook for global inflation is on the turn. A modest rise in inflation - and inflation expectations - from their very low levels in the US and UK will be echoed through the rising yields in the global government bond market.

This is especially the case when combined with exhaustion from monetary policy and the focus on increased levels of fiscal spending.

Yields on the US and Australian ten-year government bonds have increased by over 20 basis points since the end of September and while these moves may seem sharp, they are not nearly as dramatic as the back-up in yields experienced during the 2013 taper tantrum.

Yields on core government bonds are likely to rise but are unlikely to surge thanks to demand from insurance companies and pension funds that have been starved of safe yield bearing assets for many years.

Government bonds hold a fundamental position in any portfolio as a diversifier, but play a diminished role in providing income.

The perceived riskier areas of the fixed income market provide some income relief. Spreads in investment grade and high yield credit have narrowed to their historical averages but can tighten further.

The performance of emerging market debt this year has been staggering. US dollar denominated debt returned nearly 15 per cent in the first nine months of the year and investors may be wondering if they have missed the rally, however the improvement in growth prospects and upward revision to corporate earnings suggests that there are still opportunities for investors.

Kerry Craig is a global market strategist at J.P. Morgan Asset Management.