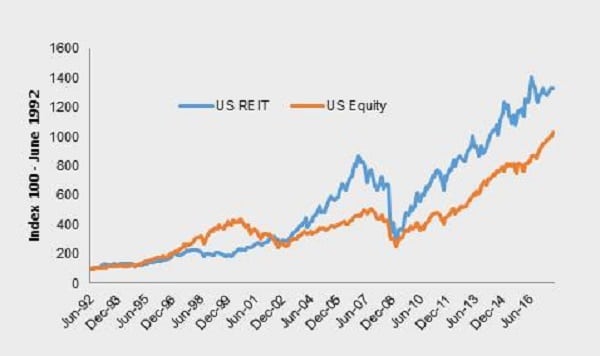

For instance, over the past 25 years, US listed real estate has outperformed US equities, as shown in the chart below.

This is not just a US phenomenon. The results are similar for global listed real estate.

In Australia, REITs have not quite kept pace with equities, which is not surprising given the banks and resources super cycles.

But direct residential property in Australia has significantly outperformed Australian equities — much to the chagrin of many equity managers that have called the sector a bubble over the past 10 years.

Indeed, it is striking to note the disdain that some general equity managers have for property, from blaming real estate for the financial crisis (banks…?) to wrongly categorising it as a play on interest rates.

US REIT vs US Equity Cumulative Return Index

Constantly labelling real estate a “bubble” or “interest rate play”, rather than recognising it as a tried-and-tested store of wealth anchored to ever-increasing replacement costs, means a large pool of equity funds simply bypass the opportunity.

This in turn leaves the asset class undervalued (and under-appreciated) relative to general equities, giving it plenty of room to outperform over time as the cash flows outweigh perception.

Equities and ‘creative disruption’

A recent statistic quoted in The Wall Street Journal was that just 30 stocks (out of a grand total of 25,782) have accounted for one-third of the cumulative wealth generated by the US stock market between 1926 and 2015.

In addition, the top 1,000 performers over this period (4 per cent of total companies) account for 100 percent of accumulated wealth.

Amazon was cited as one of the top 30 stocks, highlighting the actual cost of owning equities: business obsolescence. It could be said that rather than creating wealth, Amazon has transferred it — from existing retailers, traditional media and other sectors.

Looking at the 30 constituents of the Dow Jones Industrial Average today, only half of the current constituents were in the index in 1992. And only two were in the index in 1929 (for those interested: General Electric and ExxonMobil).

Equities are about “creative disruption”, while real estate simply maintains its share of income. The rate of obsolescence across quality real estate is remarkably low. Land in New York, London, Tokyo and Sydney was valuable in the 1930s and is just as, or likely more, valuable today.

There is no reason to doubt that the claim of well-located land on the economy will be relatively stable over time, as it will always remain one of the critical factors of economic production.

This brings us back to our original point: the long-term outperformance of real estate compared to equities. Well-located real estate that is growing in line with the economy, plus a yield enhanced with the benefit of moderate leverage, can compete with long-run real earnings per share with less risk of obsolescence.

On top of this, a case can be made that equity valuations look vulnerable from current levels, not only from a price/earnings perspective, but the massive tailwind of ever-increasing profit share which will, at some point, end and possibly reverse (especially given the rise of populist politics).

What does this mean for investors? Real estate (listed or otherwise) tends to be characterised as a “proxy for bonds”, a “yield play” and a “defensive asset class”. However, for longer-term investors, the sector represents a store of real (inflation-protected) wealth.

If carefully selected and financed, this avoids capitalism’s brutality of obsolescence, which in turn provides the asset class with a significant advantage relative to equities over time.

While many investors’ portfolios are equities-centric (whether domestic or global), we believe investors would be well served to consider diversifying into global real estate.

Chris Bedingfield is also a portfolio manager at Quay Global Investors, a Bennelong boutique.