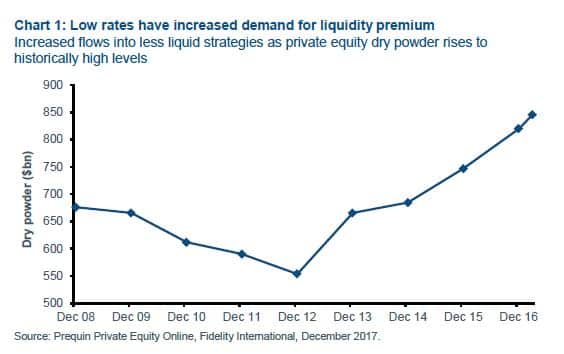

In a world of ultra-low yields, investors have been chasing liquidity premia, fuelling a rise in private market investments.

But higher historical returns should not be misattributed to illiquidity when they have been at least partly cyclical (and are unlikely to last).

What’s more, the corporate landscape is changing faster than ever before – requiring more of a buffer, not less.

From public to private

Over recent years, investors have increased their allocation to unlisted or private markets.

One of the key reasons for this, at a time of ultra-low yields, is that many investors believe they can earn a liquidity premium by putting long-term capital at risk in strategies such as private equity, real estate and infrastructure.

As a result, these privately traded asset classes have grown while the volume of shares issued in public markets has shrunk.

The number of listed companies across major equity markets is declining, and managements of many listed companies have resorted to ‘value transfers’ to shareholders via sizeable share buy-back programs.

In fact, this shift has been so stark that many observers are now wondering about the long-term prospects for listed equity markets.

I think it is worth taking a step back, to examine whether this trend is cyclical or structural, and, importantly, where some of the risks in the flows from public to private markets may lie.

The destination or the journey

In this market cycle, investors have been as, if not more, concerned with the shape of the journey than the destination. They have paid an ever higher price for predictable, low-volatility securities.

It is likely that this has played an important part in attracting flows to these alternative asset classes.

The spread of underlying outcomes in private equity portfolios may be wide, but investors tend to focus on internal rates of return (IRRs) offered by such strategies, which are typically smoothed over the life of the fund.

Additionally, over the last 10 years of generally rising asset prices, these strategies have been able to demonstrate healthy absolute returns.

Given this combination of rising markets and the smoothing of returns, it is unsurprising that the sector has drawn such strong flows.

And there’s more to come: private equity funds currently have almost $1 trillion in committed, but as yet undeployed capital.

Valuing liquidity

Valuing liquidity is far from straightforward.

Still, for investors weighing up alternative asset classes, it is important to separate those parts of returns that can be realistically attributed to a liquidity premium.

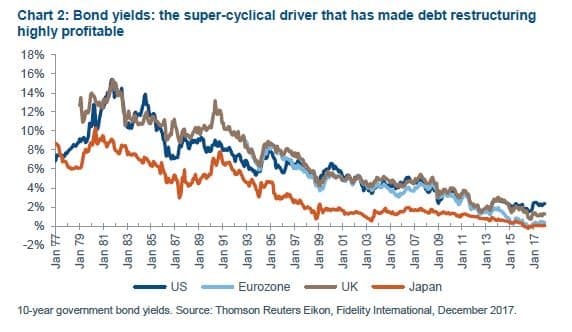

It turns out that debt restructuring and maturity extensions account for a material component of achieved returns for many private equity, infrastructure and real estate portfolios, either at the project or company level.

But bond yields can’t continue to fall as they have in the past 30 years, and private equity can’t continue to rely on the income stream from ‘terming out’ debt.

This means there is a high probability that the perceived total ‘liquidity premium’ earned in the past is unrepresentative of future returns.

More or less?

This leads to two simple observations:

- First, elements of past returns in illiquid asset classes may be more challenging to achieve in the future (given that the cost of debt may be starting to reverse); and

- Second, the revaluation of these strategies, given flows over recent years, means that the liquidity premium on offer today is, in any case, lower than in the past.

So should investors be demanding more, or less, to compensate for illiquidity? Let’s stay with private equity because it is particularly illuminating.

Many private equity funds today offer similar propositions along these lines:

- Given current valuations, IRRs are expected to be lower. Crucially, as many of the funds will tell you, that is fine as clients are happier with lower returns given low risk-free rates and low yields on offer elsewhere (happy with less);

- The funds are comfortable with higher valuations as they are confident in their ability to add value to assets through operational expertise (happy with less); and

- Many funds are extending timeframes, locking up money for longer periods, to achieve returns and put the backlog of money to work (happy with less).

But does this really make sense?

Across the corporate sector, the pace of creative destruction is accelerating as new technologies, greater choice and lower switching costs lead to rapidly changing customer behaviour.

The likelihood that a business’s competitive position, its pricing power, and, hence, its intrinsic value change is now greater than ever before.

If the risks around tying up capital in individual companies for longer periods are greater today than historically, investors should be demanding more, not less, to compensate for illiquidity.

This strikes me as a fundamental inefficiency in the market today.

Keeping it simple

Some of these observations apply not just to private equity but to other unlisted or private securities, too.

While the principle of long-term investing is sound, it is worth remembering that a liquidity premium exists for a reason – to keep it very simple, it’s much easier getting in than getting out.

Several factors have contributed to the returns, and hence the attraction, of private markets over public markets in recent years.

There is a risk, however, that many of these factors will turn out to be more cyclical than structural.

Across the corporate sector, and in the broader economy, the facts are changing at a much faster rate than ever before, so it is important to think carefully before giving up the ability to change your mind.

Paras Anand is the chief investment officer for European equities at Fidelity International.