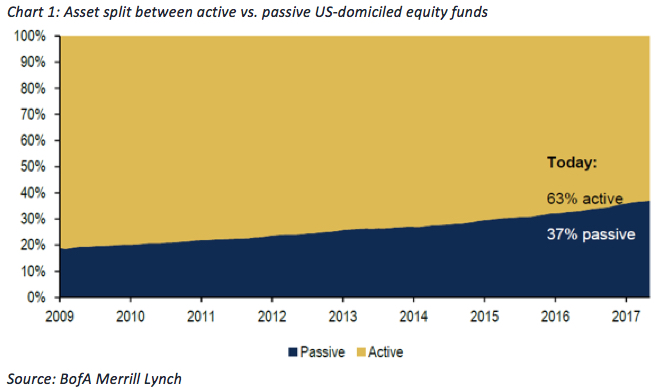

The increase in passive investing in the last 10 years has been phenomenal. Today, passive is up to 37 per cent of total funds under management (FUM) in US equity funds, from less than 20 per cent in 2009.

There are fair arguments for this to be the case, of course – notably the fact that passive investing comes with a lower headline fee.

When considering compounding, fees can add up over time, particularly if the active manager is not adding value.

Notwithstanding that, when investing in a passive index replicator, by definition there is no active alpha; and when you add fees on top, albeit low fees, you are guaranteed to underperform the market.

The most popular exchange-traded funds (ETF), those that purchase stocks based on market capitalisation, are used in portfolio construction as cheap market exposure.

In a cap-weighted index, the higher a stock goes, the more it is worth, the higher its index weighting and the more passive funds must purchase.

With cap-weighted indices, as a stocks market cap increases, a passive vehicle must buy more; as its market cap falls, the required holding decreases. In essence, buy high, sell low.

Arguably, managed active funds have the same issue given many of them use market cap benchmarks. The difference is that an active fund has a choice.

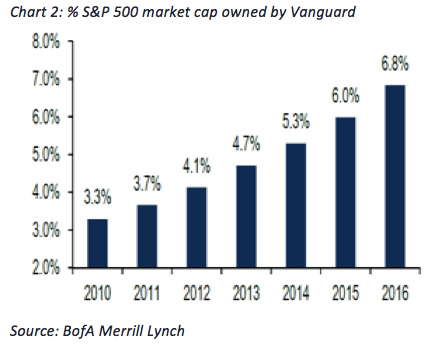

However, ETFs are not going away. Vanguard now owns 6.8 per cent of the SPX market cap (below), more than 5 per cent of the share register in 490 stocks in the S&P500.

A recent Citigroup research piece shows that passive investors own 22 per cent of the US market free float.

A key finding from a recent Rainmaker adviser survey is that while 35 per cent of advisers are yet to implement ETF strategies in their business, 94 per cent of respondents are either highly or somewhat likely to ramp up their use of ETFs in the coming year.

Oaktree Capital Management co-founder Howard Marks said, “What should we think about the willingness of investors to turn over their capital to a process in which neither individual holdings nor portfolio construction is the subject of thoughtful analysis and decision-making, and in which buying takes place regardless of price?”

As well as an implicit lack of price/value as a basis for investment, we also need to consider liquidity.

If a passive investment vehicle owns a large portion of a company’s free float, and will only buy or sell shares based on some type of signal, such as an increase or decrease in market capitalisation, should we consider that free float?

One bank research report tells us that stocks that have a large portion of their float held in passive investments have seen their volatility increase, arguably because their true liquidity is lower.

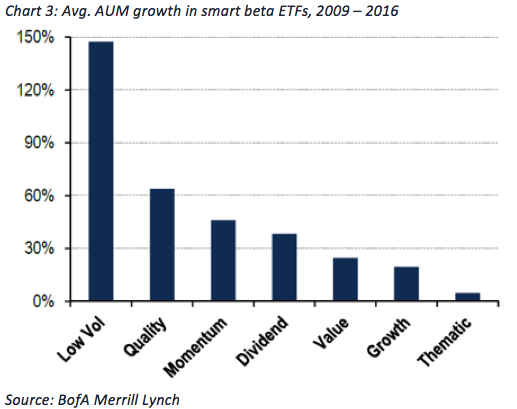

ETFs can also be designed around themes or flavours. While they run the risk of being populist and clichéd (smart-beta, anyone?), they have also proven very popular.

As an example, the 'low-volatility ETF' has been very successful over the years.

Here, we can see the average annual growth in smart beta ETFs between 2009 and 2016.

Since 2009, low volatility ETFs have had 150 per cent annual asset growth. How does it work?

Simply, the strategy systematically screens the investible universe and invests in those stocks that exhibit low volatility.

As a general statement, valuation is not an input. It has been sold as a defensive strategy.

The strategy has been a good source of outperformance, particularly in Australia.

But one must question how much of this 'alpha' has been driven by its own popularity, as fund inflows lead to more buying, which lead to higher prices. Having no regard to valuation leaves a strategy open to the impact of momentum, good and bad.

At some point, fundamentals matter. This has been evident more recently, with low volatility strategies performing poorly.

This is just one example of what you could call a hidden risk in the strategy, particularly in one that is generally added for its defensive (low beta) characteristics.

Passive investments can provide cheap exposure (in terms of fees), but there are always going to be hidden risks built up when valuation is not the key metric.

Dan Bosscher is a portfolio manager at Perennial Value Management.

Disclaimer: Please note that these are the views of the writer and not necessarily the views of Perennial.