How did we get here? The financial sector is supposed to support the long-term growth of the real economy. Investment professionals are supposed to allocate capital productively, yet the rise of passive investing is encouraging the exact opposite. Furthermore, financial markets today are driven by short-termism and dominated by speculation.

In practice, investing has become so detached from the real world that it is more akin to a fantasy land, inhabited by a growing number of peculiar characters undertaking nonsensical tasks.

When a mum and dad investor’s hard-earned dollar heads down the hole into today’s Financeland, it is likely to go on a journey similar to Alice’s in Wonderland, encountering strange financial beasts and involuntarily taking part in circular nonsense. Their savings have every chance of drowning in dark pools, being pounced upon by ultra-low latency traders and falling prey to Alligator Swaps, Canary Calls and Iron Butterflies.

There is one key difference between Wonderland and Financeland. While Alice returns to the real world unscathed, the same cannot always be said for mum and dad investors’ money.

As for the investment community, the challenge is to look with eyes wide open at what’s gone wrong in Financeland and decide where we want to take it from here.

Blindfold Capital Allocation

Financeland’s absurdity has three main underpinning features. The first is that society’s savings are being increasingly allocated with eyes-wide-shut via an index or exchange-traded fund (ETF).

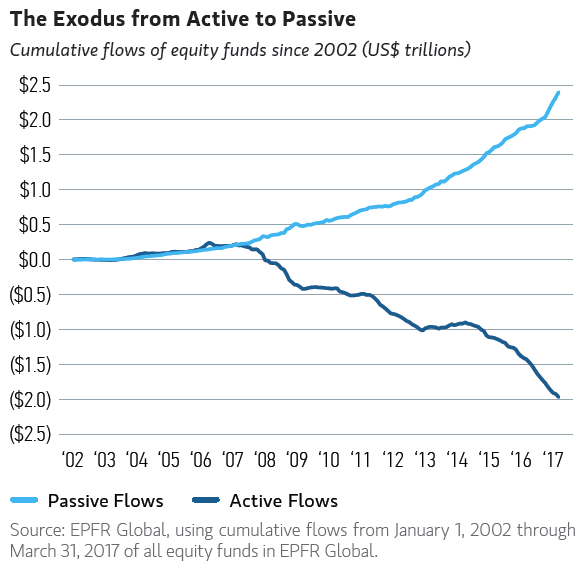

Figure 1: The Exodus from Active to Passive

Source: Morgan Stanley

In many ways, active managers have been responsible for their own downfall. Short-term incentives, product proliferation and closet index hugging have all driven clients towards blindfold investment.

Most index and ETF funds make no attempt to work out whether the companies receiving this scarce capital are intending to use it productively. Thus, poor quality companies, whose activities are counter to the long-term benefit of societies, are the easy recipients of capital.

Surely the point of a financial industry is to strive to allocate capital productively, not to shut its eyes and pass it on indiscriminately.

Short-termism

The second absurdity of Financeland is its short-termism. Time horizons have collapsed. If the trend continues, time horizons will reach some kind of perpetual motion, where capital is instantly and constantly recycled around the financial system, without pause. Arguably we are there already, given the prevalence of high frequency trading.

As Michael Lewis’ excellent and frightening book Flash Boys highlighted so clearly, financial markets today are dominated by speculation, not investment.

Short-termism and speculation are bad for investors for two reasons. First, they have created too many agents whose purpose is to grab as much money as possible, rather than productively put it to good use. There are no ‘liquidity’ benefits to society that occur from high frequency trading.

Secondly, the damage wrought by short-termism reaches far back into the real world. Again, this is well-documented. Given their dependence on such short-term, transient, unreliable capital, many listed companies are under pressure to run their businesses simply for the next three months, rather than the next 10 to 20 years. This is not good for society or investors.

The wrong kind of alignment

The third aspect of absurdity in Financeland is the obsession with financial alignment. Just as the Queen of Hearts could only think about chopping off heads, so are today’s Financelanders obsessed with financial alignment.

‘Skin in the game’ is perhaps the most commonly used method today to try and address the principal-agent problem in shareholder capitalism. It applies not just to company managers but to fund managers as well. But do retail investors really want to hand over their hard-earned savings to professional investors who are only going to try their best because they are looking after their own money at the same time?

In Financeland it is assumed that humans perform better the more they are paid. In the Real World this has been proven not to be true as highlighted by Dan Pink’s excellent Ted talk. With the exception of simple, repetitive tasks, financial incentivisation can often lead to poorer outcomes including diminished intrinsic motivation, lower performance, the crowding out of good behaviour, unethical behaviour, addictions and short-term thinking. All these are easily recognisable traits within Financeland.

Solutions

If blindness, short-termism and misplaced alignment are the ailments of Financeland, what are their cures? A number of ideas have been suggested over recent years.

Three in particular stand out as worthy of immediate consideration. Most compelling is the creation of a series of new electronic long-term stock exchanges designed to replace the void left when the old stock exchanges metamorphosed into today’s financial casinos. What should such a stock exchange look like? There would be no short-selling or financial derivatives and a minimum holding period of a day. These features would go a long way to ensuring investment drowned out speculation.

The second compelling idea is around the restriction of liquidity. The majority of equity investment has no notice period. Introducing a simple notice period of a week or month on all regulated investments would deal a significant blow to short-termism. Listed equities are in theory a way of reallocating society’s savings for the long term. Why then do investors in equities need to be able to buy or sell instantly? We are used to time deposits when we entrust our savings to the bank. Why not time investments too?

The third solution worth considering is improving alignment. Rather than focus on the financial alignment between managers and shareholders, emphasis should be placed instead on real alignment with the broader society from which real companies and financial companies both derive their licence to operate.

The greatest weakness of most remuneration schemes is that they end up crowding out much more important non-financial motivators for performance around the intrinsic quality of the job itself.

Dan Pink argues that motivation of employees should revolve around three elements: “Autonomy: the urge to direct our own lives. Mastery: the desire to get better and better at something that matters. Purpose: the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves.” In other words, jobs are not a means to an end but an end in themselves.

Very few companies think this way, particularly in Financeland.

All of these ideas appear at first glance peculiar. It is only when we are able to stand back from Financeland and recognise the absurdity of what it has become that ideas such as long-only stock exchanges, time investments and the importance of purpose appear eminently sensible suggestions for reconnecting Financeland to the Real World. Alice finally woke up. It is time we did too.

David Gait, managing partner, Stewart Investors