There is actually no industry standard definition for alternatives with the asset class often defined by what it isn’t, namely stocks, bonds or cash. Some, ourselves included, add real estate and infrastructure to that list, preferring to consider these separate asset classes.

What this leaves behind includes private equity, commodities and hedge funds as well as tangible assets like art and coins and any number of niche financial assets.

How do you characterise a hedge fund?

Long/short equity, global macro, systematic, merger arbitrage and event driven are just a few of the strategy types that fall under the banner of hedge funds although some of these we don’t consider to be true alternatives.

An important characteristic of a hedge fund should be the low correlation of its returns to those of stocks and bonds; however, many larger funds (often long/short equity strategies) simply replicate equity market returns with an overlay of expensive fees.

Why a diversified portfolio is key

In general, if a hedge fund has a correlation with equity markets of 0.4 or higher, it’s not one we will invest in because it’s unlikely to add enough diversification to a portfolio to justify the risk or the increased fees. An example of this might be one of the many multi-billion dollar long/short equity strategies that employ a rigid 130 per cent long, 30 per cent short strategy. Using the proceeds from borrowing and selling stock to the value of 30 per cent of the fund’s capital, the manager now has 1.3 times the capital to deploy in buying stocks. Unless the short positions were to move in very different ways to the long positions, the fund investor may end up with a similar exposure to a long only fund.

In part, asset management firms are attracted to a 130/30 structure over a more flexible strategy that might be able to fluctuate short positioning with more freedom because it’s well known that capacity to short sell is never as large as capacity to invest on the long side. More capacity means higher management fees but usually diminishes the prospects for outperformance. The short book may serve only to provide funding a larger long book and leave the investor with a similar outcome to a long-only strategy and yet, because it’s a hedge fund, the manager is able to charge much higher fees.

Long-term valuations across traditional asset classes are high and, in the past, this condition has tended to be associated with lower future returns. With this in mind, allocating to the right alternatives is as important as ever and hedge funds offer one way for investors to access alternatives in a more liquid form.

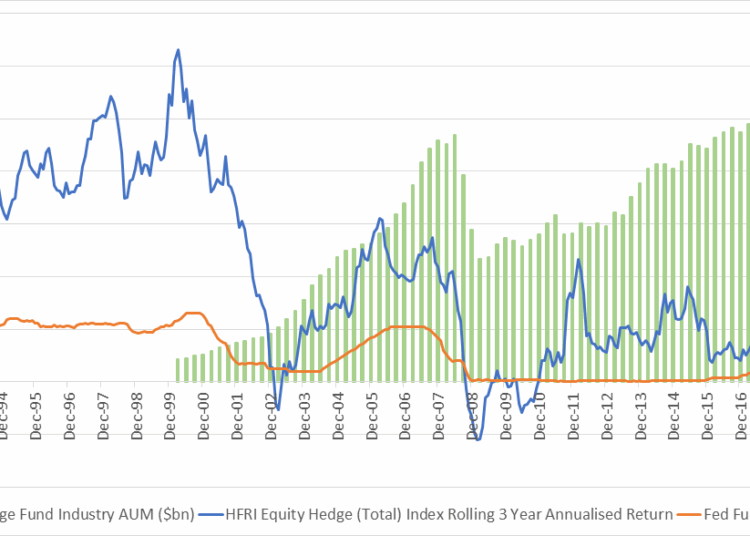

Unfortunately, the hedge fund industry has been blighted by poor returns over the last 15 years primarily because most hedge fund strategies have grown too large, with managers attracted to the industry by the prospect of high fees. In 2000, the global total invested in hedge funds was a little over $200 billion, today this figure stands at almost $3 trillion. Quality data on global hedge fund AUM prior to 2000 isn’t available but it can be reliably assumed that the figure never exceeded about $250 billion until late in that year. Since then, the figure has grown to almost $3 trillion.

As the chart below illustrates, lower interest rates over the last decade have had some dampening effects on absolute returns for various hedge fund strategies but it’s likely that the growth in the size of hedge funds explains more of the variance.

Source: Hedge Fund Research, Inc.

Selecting the right fund manager

The more regular outperformance of the small hedge funds of the 1990s provides evidence as to why smaller hedge funds with the right attributes are still able to outperform today. This is why selecting managers that adhere to realistic capacity constraints and have significant personal investments in their strategies is the most important consideration as an allocator.

Tom Collinson, portfolio manager, Lucerne Investment Partners