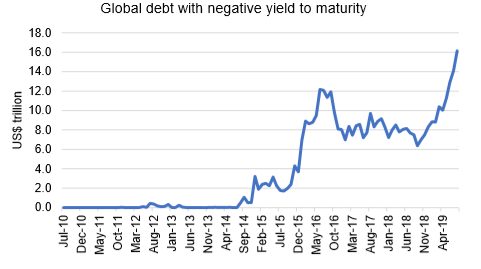

This is highlighted by the recent increase in negative-yielding bonds. As per the chart below, the amount of global bonds with a negative yield to maturity has surged to represent a record US$16 trillion in value.

Source: Bloomberg, Quay Global Investors

What does this mean?

For some, it’s an example of a “bond bubble”. Holding a negative-yielding bond to maturity means certain economic loss. The only potential gain is to onsell the bond for an even lower yield (i.e. finding a greater fool) before maturity, passing the certain loss to the buyer. This is not a bad definition of a bubble.

However, we believe the rise of negative bonds yields is more complex. It begins with how central banks set interest rates.

Central bank interest rate policies drive bond yields

In most developed currency-issuing countries, the central bank is the sole price setter of short-term interest rates. It does this by declaring an interest rate target and then conducting open market operations to manage cash reserves held by the banks, to encourage bank borrowing and lending at the target rate.

For example, in Australia the current target cash overnight interest rate is 1.0 per cent (at the time of writing). This is the rate at which the RBA wants banks to lend to each other, overnight, on an unsecured basis. The official cash rate is also the rate banks receive on cash held at the RBA. However, in Australia banks are penalised 0.25 per cent if they hold too much or too little cash at the end of the day.

As banks are profit maximisers, they avoid the penalty rate by lending or borrowing excess cash to each other at the target rate (except in extreme circumstances where bank asset values become significantly impaired, at which time banks forgo profit maximisation and choose capital preservation).

Since banks receive 1 per cent on lending in the interbank market, they are unwilling to offer more than 1 per cent across their deposit book. Why attract deposits at greater than 1 per cent cost when the rate of return on reserves/exchange settlement accounts is 1 per cent or less? In this way, the central banks really control the deposit rate (not the lending rate). The lending rate only reduces to the extent banks maintain the same net interest margins.

As we learnt with Modern Monetary Theory, the universal laws of accounting mean that non-government financial savings are equal to net government debt – to the cent. Financial savings are further defined as cash or government bonds.

The subtlety is that for a given level of government debt, non-government savings are fixed. One person or entity may wish to spend their savings (on a car or holiday etc), but at a macro level, these savings are simply passed onto another entity in the form of spending. Alternatively, one person may decide equities is a better bet than cash – but upon settlement of their chosen shares, the seller of those shares now ends up with the cash.

This means at a macro level, savers have a binary choice: cash (of various maturities) or government bonds (of various maturities). If investors believe central banks will eventually pursue (or maintain) an official negative cash rate, buying negative-yielding debt is not necessarily irrational. They are simply trying to minimise losses.

Put another way, government bond yields are nothing more than an indifference point relative to long-term cash expectations.

So, while central banks control the cash rate directly, their actions and price signalling indirectly control long-term rates.

Are sovereign bond yields a bubble?

Viewed via this framework, the answer is no. That doesn’t mean buyers of negative-yielding bonds will not lose money. They certainly will, if held to maturity. However, if expectations are correct, they will lose the same amount of money as if they were holding cash over the same timeframe. Choose your poison: a certain loss (bonds) or an uncertain loss (cash).

How did we get here?

For the past 30 years to 40 years, the orthodox approach to macro-economics has been:

1. Governments to “get out of the way” and seek to balance the budget over the cycle

2. Outsource the role of price stability (inflation) and employment to central banks

3. Central banks to meet this objective via monetary tools.

“Monetary tools” initially meant to regulate money supply. But as monetary authorities have learnt, money supply and credit creation is an endogenous process – that is, bank loans create deposits. Upon recognising this, the central bank’s primary monetary tool became price (setting the interest rate).

In most economies, the non-government sector is a net saver. This means the government must run deficits over the cycle, or the country must run external account surpluses (or both). Not doing so means new money has to fill the gap. Step in private sector debt.

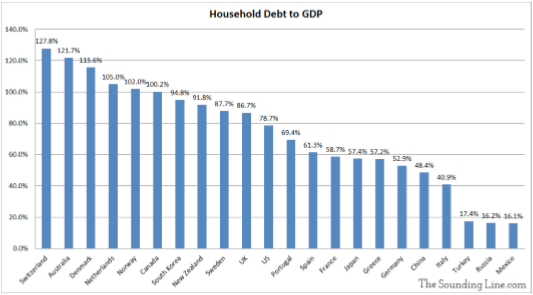

It’s no coincidence that most developed countries have very high levels of non-government debt. In order to keep the machine moving while governments self-impose fiscal constraint, central banks need to keep cutting rates to sustain incomes and encourage new credit growth. It is therefore no surprise to eventually see interest rates tend to zero (and below) in these very same countries.

The unwillingness of currency-issuing governments to use their currency-issuing authority to respond to economic shocks has placed all responsibility on price and employment stability to the central banks, who are responding the only way they know how – by pushing interest rates lower, and in many cases below zero. Bond yields have rationally followed.

The entire mess of using monetary policy in place of fiscal policy over 30 years can be summed up in one almost perfect tweet I read last month.

“Negative yields are basically the market’s way of taxing people who oppose fiscal stimulus because they don’t want to be taxed.” - Joe Weisenthal, Bloomberg, 31 July 2019

The end game

It’s been an incredible 12 months in financial markets, from “interest rates are certain to rise” to “deflation and low interest rates are here to stay”.

We have always been more dovish on interest rates versus the consensus – from our prediction that Australian interest rates would head to zero (February 2015), to exercising care for the so-called ‘“reflation trade” (April 2017), to our non-consensus call that the next move in Australian interest rates would be down (November 2018).

However, we believe there is a change coming. We believe inflation will return because the role of central banks in managing the economy will change dramatically.

Inflation is not dead: in fact, creating inflation is very easy

Part of the “lower for longer” thesis comes from the belief that inflation is not returning any time soon. This idea stems from the relentlessly incorrect calls from mainstream economists who believed quantitative easing was “money printing”, and +US$1 trillion deficits along with low interest rates were inflationary.

None of these predictions came true, because mainstream economics does not accurately include the monetary system into its models, or understand that the transmission mechanism between central bank policy and the real economy is incredibly weak.

For a currency-issuing country like Australia (or the US, etc), money is a public monopoly. As taught in year 12-level economics, a monopolist can always be a price setter. As the monopolistic issuer of the currency, the fiscal arm of currency-issuing governments can always set the price if it so chooses. The only impediment has been political will.

For example, the Australian government could enact a national jobs guarantee, and with its fiscal powers set the minimum wage for such a guarantee at $30 per hour (versus the current minimum wage of $19.49 per hour). Instantly, wages would reprice across all levels of skill and industry.

This could be done tomorrow, and hey presto: we would have inflation. The only constraint is political will.

One of the reasons we wrote our MMT papers earlier this year is that we feel for the first time in 40 years, the economic tide is changing. Economists, market participants, elected officials and other commenters are beginning to realise that the traditional tools of central banks will not be enough to offset the next economic crisis.

We know negative interest rates don’t help. We know quantitative easing has been all but useless in Europe, Japan and the US. And some bemoan that most governments have run out of money and thus won’t be able to respond with fiscal stimulus if we were to suffer another downturn.

The 2017 Trump tax cuts changed everything

Globally, the conservative side of politics has been noted for “fiscal conservatism” – that is, to reduce the size of government and balance the budget over time. And for a large part, progressive politics has tried to follow suit.

There were times this stance did not always gel with reality. For example, Republican George W Bush increased the deficit after Democrat Bill Clinton balanced the budget and eliminated federal debt. But these moments were generally explained away as one-time events. In the case of Bush, the war against terrorism justified the one-time surge in government spending.

But the Trump tax cuts were different. There was no immediate threat of terrorism or war to justify increased spending, and the economy was in good shape. The argument was the tax cuts (generally to companies and high income earners) would spur jobs growth and increase wages – neither of which has really happened.

What has happened is a substantial increase in government debt, for little or no real change in momentum in either the labour market or the economy. Despite the massive increase in government debt, the yield on the US 10-year Treasury (at the time of writing) is near record lows.

When the voting public understands the government is not a household, there will be a seismic shift in markets

As we learned with our MMT papers, a currency-issuing government is never financially constrained. Therefore the surge in US government debt along with near record low bond yields is not surprising to us.

But the public doesn’t understand MMT – and nor do many economists or market participants. Based on the public reviews of MMT in the financial press, we do not hold out any hope the public or mainstream economists will understand it anytime soon.

What the public is beginning to understand, however, is that the politics of fearing the “debt and deficit” is now largely discredited. Upon this realisation, it’s only a matter of time until the obvious question will be asked: “If the government can increase the deficit by US$1 trillion without a surge in interest rates or inflation, then why can’t the government use its spending powers to increase the deficit by $1 trillion for policies that the wider public actually [wants]?”

By increasing the deficit in favour of households (who are most likely to spend incremental money they receive) rather than the wealthy (who are most likely to save incremental money they receive), there is, for the first time in a generation, the real possibility that modern western economies can achieve near full employment, improving wage gains and a corresponding return of inflation.

When that happens, those “lower for longer” bond holders and equity investors need to watch out – the losses could be staggering.

How does this affect Quay’s investment process?

At Quay, we are first and foremost stock pickers with a thematic overlay. The potential for increases in interest rates doesn’t worry us. In fact, a return of inflation would be an overwhelming positive for long-term real estate investors as we have previously highlighted.

However, part of our themes and investment positioning has been based on:

1. The shrinking middle class and low wages growth (negative impact on malls)

2. Shrinking home affordability due to high student debt and low wage growth (positive for affordable apartment REITs and single-family homes)

3. Re-urbanisation of major cities as workers seek better jobs (positive for apartments and storage). With the possibility of governments rediscovering both their fiscal powers and social vision, policies such as lower university tuition fees could mean these themes may well reverse at some stage. We are always keeping an eye out for what could change.

In our view, the seismic shift from relying on monetary policy to using fiscal policy is almost certain and will potentially have major ramifications for all markets and strategies well beyond the bond market. As we enter the 2020 US presidential election year, the emerging political debates and electoral response will be worth watching.

Chris Bedingfield, principal and portfolio manager, Quay Global Investors