Far from being a rogue operator, Evergrande is emblematic of China’s debt-fuelled expansion, with property now comprising 13 per cent of GDP and 20-25 per cent of growth. It’s this once booming property market which underpins Evergrande’s rapid ascent, however a recent slowdown in the Chinese economy has exposed the company’s crippling levels of debt.

Pushing on a string

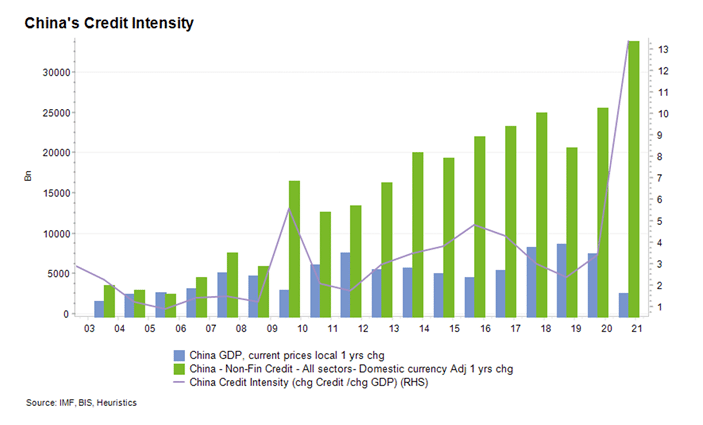

The below chart highlights China’s growing reliance on debt to generate GDP growth, with a clear divergence evident in recent years between the volume of debt required to generate a dwindling amount of GDP. Importantly, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) has sufficient resources to backstop Evergrande’s liabilities and ringfence potential spill over into other markets; however, the authorities are instead making a conscious decision to deleverage, de-risk, and make an example of this behaviour.

In recognition that property developers had been sleep walking into disaster, the “three red lines” policy was introduced in August 2020 to improve the financial health of the real estate sector. The three red lines were imposed on property developers to help stem growing debt levels and unsustainable price increases, and include:

- Liability-to-asset ratio (excluding advance receipts) of less than 70 per cent;

- Net gearing ratio of less than 100 per cent; and

- Cash-to-short-term debt ratio of more than 1x.

Slowly, and then suddenly

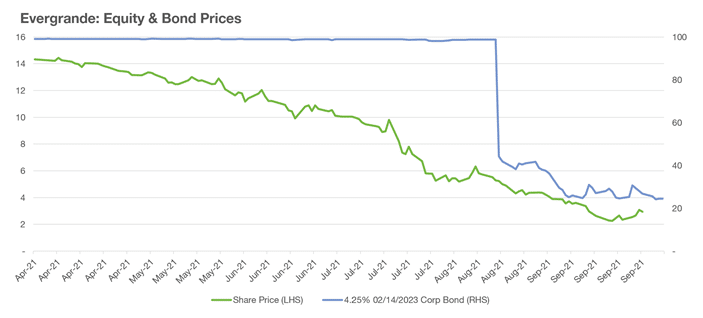

Once seen as the poster child for China’s property boom, Evergrande soon found itself in the authorities’ crosshairs after having contravened all three red lines. The property behemoth’s insatiable debt binge quickly saw liabilities swell to US$300 billion, with the market now pricing in a high likelihood of default. Consequently, Evergrande’s acute liquidity stresses and increasing difficulty funding operational obligations and coupon payments has resulted in the price of its equity and debt securities cratering.

Exacerbating Evergrande’s woes has been the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) relentless pursuit of “common prosperity”, which saw price limits imposed on new property developments and harsh penalties for developers who failed to deliver projects on time. Where previously it had been widely assumed that Evergrande was simply too big to fail and that an implicit government guarantee would backstop the company, this optimism quickly deteriorated as the authorities remained silent while the cash-crunch loomed.

The triple header

This culminated into the first negative monthly return in 11 months for the Australian share market, as fears over a systematic meltdown had investor anxieties riding high. Market commentators have attempted to prosecute the case that this is China’s “Lehman moment”, although a recent liquidity injection from the People’s Bank of China has somewhat quelled these fears. While the prospect of a catastrophic collapse now looks less likely, a restructuring of Evergrande appears imminent, albeit with investors likely copping a significant haircut.

The magnitude of the ripple effects for investors will hinge on whether the restructure is orderly, although the consensus suggests that the CCP will act to prioritise social stability. We expect there to be acute impacts within the high-yield credit sector in China, particularly anything tangentially related to the property sector.

To date, there has been some mild contagion effects, with lenders, insurers and suppliers most exposed to Evergrande understandably suffering the most. Broadly, the domestic situation in China appears highly volatile with property prices most exposed to asset deflation – although given the negative implications for social cohesion, the likelihood of the CCP allowing this to transpire appears low.

Cut and run

While not our base case, the seizing of credit markets could be the catalyst for broader defaults among property developers as access to offshore financing evaporates. Notably, this represents an extreme left-tail scenario and would likely prompt regulators to provide support to prevent chain defaults. The most favourable scenario would have the government intervene to maximise asset values while balancing the competing pressures of moral hazard reduction against financial contagion.

Investors should expect to see some spillover effects as China’s construction industry is heavily reliant on our domestic iron ore, which has halved in price in recent months with Australian miners caught in the crossfire. However, given at least half of Evergrande’s liabilities relate to deposits from prospective buyers, it’s difficult to conceive a scenario where the CCP doesn’t resolve these favourably, given the societal ramifications of the authorities presiding over thousands of buyers losing their life savings.

Ever-(not)-grande

Pleasingly, Zenith portfolios hold no exposure to Evergrande’s debt or equity securities, which demonstrates the importance of selecting high-quality active managers to navigate stressed markets. This is further emphasised through Evergrande representing a disproportionately large weighting in high-yield indices, as the most indebted issuers are perversely the largest constituents in passive allocations.

Finally, regarding assertions that China is no longer investible, we instead take a more nuanced view and rely on the expertise of our active managers to assess the ESG risks associated with investing in politically charged economies. This is best illustrated through the Evergrande slow motion disaster, where managers had intentionally avoided the property titan for years – a view since vindicated as the controlled demolition slowly unwinds.

Calvin Richardson, investment consultant, Zenith Investment Partners