Historically, there is a positive relationship between rising income and energy consumption. As emerging economies continue to develop, the demand for energy will continue to rise.

To meet the rising demand for energy and carbon emission reduction targets, countries and companies need to invest significantly in renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and hydro. The reality is that renewable energy accounts for less than 5 per cent of energy needs. The transition to carbon zero is going to require the use of fossil fuels in years to come.

It is encouraging to know that our reliance on fossil fuels will reduce significantly over time. Coal, as the highest emitter of carbon, will come under the greatest pressure. Natural gas, dubbed “freedom gas”, produces the least carbon per unit of energy among the three primary fossil fuels and is the transition fuel of choice.

Oil is the second largest source of carbon emissions. The largest end-consumer of oil is the transportation sector, specifically passenger vehicles. This is followed by trucking, aviation and shipping and then petrochemicals.

Despite the excitement over electric vehicles (EVs), oil demand is expected to remain flattish through to 2030 and gradually decline after.

Governments around the world have adopted policies to reduce carbon emissions from the transportation sector. Many have mandated the phase-out of internal combustion engine vehicles in the coming 10 years. However, this will take time. Only 10 million EVs were sold in 2020, representing around 10-12 per cent of global car shipments. Additionally, there are over one billion cars on the road. Therefore, oil demand from the transportation sector will keep on growing as traditional vehicles continue to be bought, particularly in developing countries. Although EV sales will grow faster, the volume of vehicles to displace is still high.

In the trucking, aviation and shipping sectors, it is difficult for batteries to be widely deployed to replace normal engines. It is also quite unlikely for batteries to displace aviation fuel in jets, given the high energy density required and the weight of the batteries. Despite improvements in the energy density of batteries, it will not match that of fossil fuels or hydrogen in the medium-term future.

Demand for oil will not grow like it did in the previous decades, but there will be a baseline demand for oil that will be difficult to replace in the next 10 years.

So, where does it leave the oil industry? For quite some time, there has been a dividing line between the oil majors in Europe and the US. The oil majors in Europe have been more environmentally aware. They have given consideration and weight to environmental issues in corporate planning. In contrast, the oil majors in the US have had a different mindset. Environmental issues have not been top of mind until very recently. Fortunately, many are now beginning to make the necessary changes.

Investor activism and increasing difficulties in acquiring lending or financial support for their operations have led to greater environmental awareness. Funds under management committed to fossil fuel divestment has also grown rapidly.

Even before the current wave of decarbonisation, the oil industry had been curtailing capital spending following the last cycle peak in 2014.

In view of years of under-investment by the oil industry, exacerbated by the COVID crunch and an extreme reluctance to grow capacity given carbon concerns, the industry may not be able to supply sufficient fuel as the global economy reopens.

As investors, we need to ask ourselves how we can objectively assess the advantages and disadvantages of investment in the energy sector. We examined closely the strategies of Royal Dutch Shell (Shell), the largest oil major in Europe.

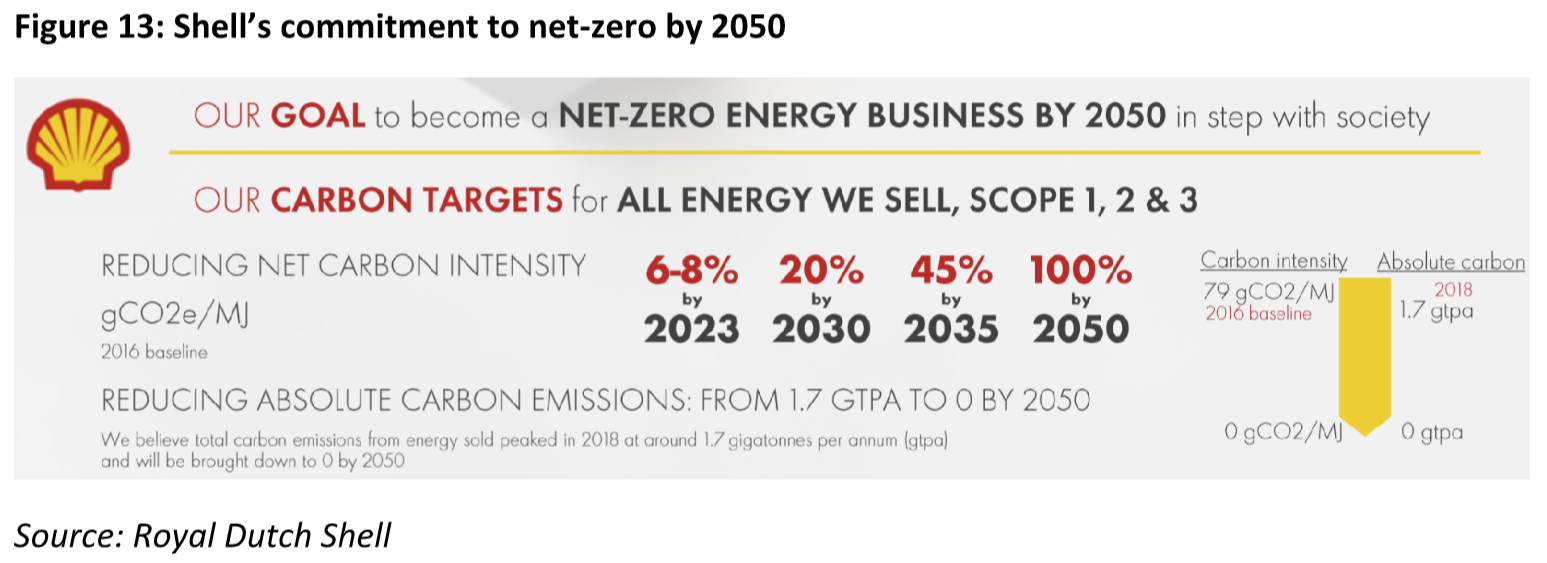

Shell has committed to reducing its absolute carbon emissions to zero by 2050. This includes Scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions.

Scope 1 covers direct emissions that are generated from sources that are owned or controlled by Shell. Whereas Scope 2 covers indirect emissions associated with the purchase of electricity, steam, heat or cooling. Although Scope 2 emissions physically occur at the facility where these are produced, these are included in Shell’s emissions as these are the result usage. Scope 3 includes full life cycle emissions from energy sold by Shell. As an oil company, the inclusion of Scope 2 and 3 emissions in reporting is particularly notable.

Shell has formulated detailed plans to reach carbon zero and has committed to publishing an update every three years until 2050. They will also routinely seek an advisory vote from shareholders on their progress. Further, executive incentive plans have been redesigned to incorporate greater weighting towards energy transition performance benchmarks.

The Shell management mentality is no longer about finding and growing resources. Rather, it is seeking to let production decline gradually by investing extremely conservatively. This could be an important signal to the rest of the industry given that Shell has one of the largest commercial resources among the majors.

Traditional fossil fuel assets are a sunset industry. Shell plans to divert cash flow towards creating businesses for the future and will invest around 40 per cent of its cash flow into new green businesses with structural growth. It will also look to invest in its LNG franchise to help a smooth transition. There are few companies in the world with the financial strength to invest as much as $5 to $6 billion a year in environmentally enhancing projects.

Overall, Shell is well placed to help their customers transition to a low carbon world. It has the expertise, scale, infrastructure, and desire to support new and cleaner application technologies such as renewable hydrogen, offshore wind, biofuels and carbon capture.

Oil demand will remain steady and natural gas will grow over the next few years. The better oil companies are drawing on their cash flow to build for the future and assist in the effort towards carbon zero.

There has been blanket condemnation of the oil industry by investors recently, flagging it as “un-investible” and not differentiating between those who are assisting with the transition and those who are not. However, the world still relies on fossil fuels for a substantial portion of its energy needs. Perhaps it’s better to source energy from a company who will work hard to reduce its emissions, rather than one who is purely profit driven.

Joseph Lai, principal, portfolio manager and CIO at Ox Capital Management.