In this paper, we convey our 10 themes for the year examining the deeper trends that will likely have major economic, political and market impact.

1. Debt proliferation

Inching higher for four decades, global debt soared during the pandemic, driven by government borrowing. Twenty-five countries, including the US and China, have total debt above 300 per cent of GDP, up from none in the mid-1990s. Money printed by central banks designed to protect lives, preserve jobs and prevent bankruptcies also inflated the financial markets, which were about the same size as the global economy in 1980, and are now more than four times larger.

This has only deepened the debt trap: societies addicted to debt find it tough to cut back, for fear of triggering a wave of bankruptcies and market contagion. Central bank mandates are generally designed to stabilise inflation and employment, but now also require that tremors in the financial economy do not negatively impact the real economy. Faced with such a dilemma, central banks need to avoid tightening too fast – a delicate balancing act that, if mishandled, could generate additional volatility and even greater stress in financial markets.

2. But no debt implosion

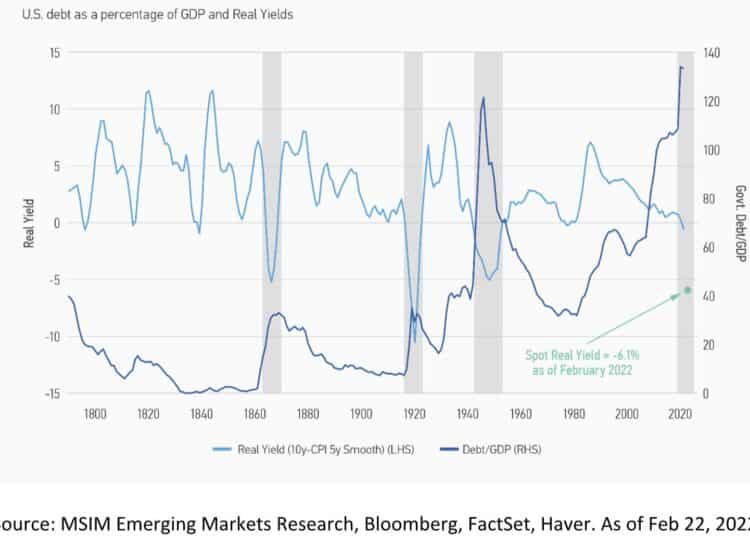

US government debt is at the highest level ever, at 133 per cent of GDP, although it reached a similar level of 121 per cent in 1946 after World War II (Display 1).

Debt spikes coincide with negative real rates

And yet, the debt service burden is not as large as it was historically. Over the past decade, average global interest rates were lower than average global nominal GDP growth rates. This has made debt sustainable across countries, a marked difference compared to the conditions before and amid the great financial crisis. The downside, however, is that higher rates will likely have a much greater impact on government and non-government balance sheets, and risk being much more damaging today than they were just over a decade ago. This could force policy makers to remain behind the curve.

Government debt sustainability depends on economic growth, budget balances and the interest cost of servicing debt. The key to debt servicing cost is the real interest rate. And with higher inflation ahead, even if nominal yields rise, real yields are likely to stay negative or low. That makes it unlikely we will witness a debt implosion, which would be the worst-case scenario for financial markets.

3. Inflation genie out of the bottle

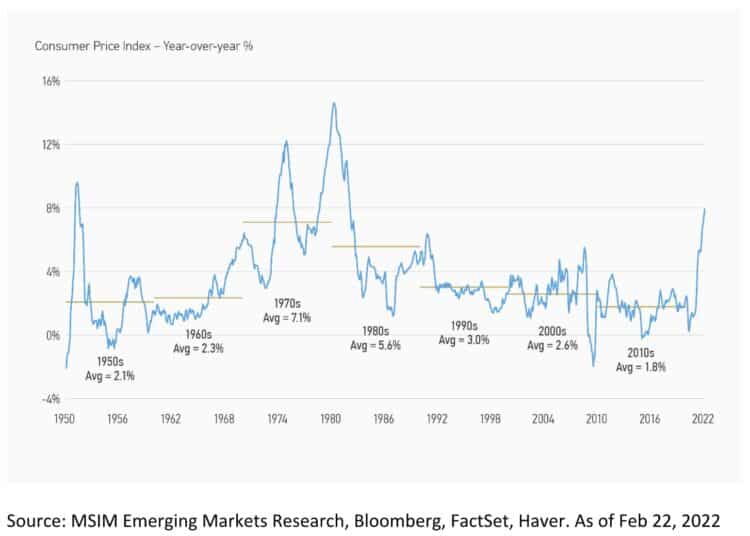

For a long time, inflation had been tamed. Last decade, inflation in the US averaged only 1.8 per cent. But as the rush of government COVID relief spending and debt last year, as well as the rise in oil prices driven by the Russian invasion of Ukraine push inflation higher, many in the media fear a return to 1970s levels of double-digit inflation when it rose to 11 per cent in 1974 and more than 13 per cent in 1980 (Display 2).

US inflation highest since the 1980s

The economy of the 1970s not only suffered from two oil price shocks (Arab oil embargo in 1973 and the 1979 Iranian Revolution), but the closing of the gold window and subsequent floating of the dollar, the unwinding of wage controls that had suppressed wage inflation earlier in the decade, and widespread unionisation that led to higher wage demands.

Since then, the US economy has become progressively less energy intensive reducing the impact of an energy price shock compared to the 1970s. The decline in union membership over the recent decades also puts a dampener on intense wage pressures.

But it isn’t the 2010s anymore either. The US does have an inflation problem, which is likely to persist. Demographic decline means fewer workers and higher wages. Deglobalisation – weakening flows of goods, money and people –reduces competition. Weak productivity growth implies higher costs. Efforts to reduce carbon emissions, is inflationary, as we note below. Sustained supply disruptions due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine will also put pressure on prices.

The bigger risk however comes from asset prices. Even when the financial markets were much smaller than they are today, their corrections could depress consumers and lead to consumer price deflation, as Japan experienced in the 1990s.

4. Greenflation paradox

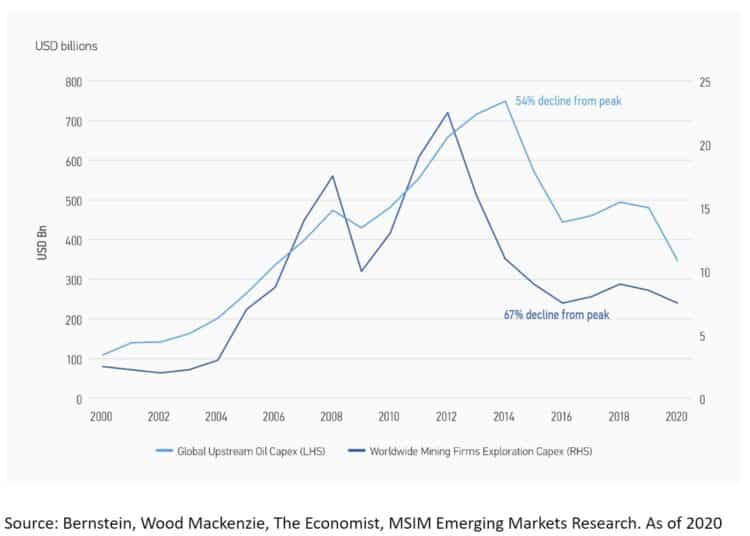

Climate change is raising demand for the so-called “green” metals like copper and aluminium, but green politics has been reducing raw material supplies of all kinds. Investment in mines and oil fields has dropped by more than 50 per cent in the last five to 10 years (Display 3). Normally, new technologies fuel a last gasp of defensive investment in old ones like electricity growth spurred a gas lighting boom in the early 1900s that continued for many years.

Global oil and mining capital expenditure has dropped significantly

Green building projects will raise demand for “dirty metals” and fossil fuel. Green politics will cut supply, inflating the cost of building a cleaner economy. The harder policymakers try to bring forward the shift away from fossil fuels, the less oil and gas exploration will take place, and oil price will need to be higher until the transition is well advanced, and that can take many years.

The curbs on Russian energy exports have seen rising oil prices and increased calls to expand domestic production. Governments are more focused on alleviating near-term price shocks, but the long-term trend is to cut reliance on fossil fuels. Both the demand and supply side dynamics in several commodities are supportive of a multi-year boom in commodity prices.

5. An emerging markets comeback

Every decade, one investment theme captures the attention of investors. The 2010s was dominated by large tech companies in the US as the US emerged from the Global Financial Crisis with a deleveraged economy, a cheap dollar and very attractive overall asset valuations.

Emerging markets (EM) have fallen off the radar after the worst decade for emerging stock market returns since the 1930s – and to makes matters worse, EM equities had another disappointing year in 2021. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index declined -2.3 per cent, underperforming the MSCI World Index by 25 per cent, due to a number of factors including: an economic slowdown driven by policy tightening, a regulatory crackdown in China, inflation overhang, dollar strength, EM currency weakness and COVID-19 shocks.

Several critical catalysts, however, should turn the macro environment positive for the EM asset class this decade. We expect a comeback for select EM equities over the next few years driven by a post-pandemic recovery, pandemic-inspired reform, manufacturing, ongoing strength in commodities and the digital revolution. Asset class valuations are at very attractive levels, with equities at nearly a 50 per cent discount based on composite metrics.

6. China 3.0

China’s old economy is slowing, weighed down by depopulation, declining productivity, high debt and the hollowing out of manufacturing industries. Going forward, growth will come increasingly from the next generation of the new, “hard tech” driven economy.

In the 2010s, China’s new economy was rising on consumer internet service giants that offered shopping, entertainment, mobile banking and the like. We believe the next turn will be to science-based industries like semiconductors, artificial intelligence, quantum computing, biotech and high-end manufacturing.

Xi Jinping is pushing for self-reliance in tech, meaning in particular less reliance on the US in order to localise supply chains. His drive to make China carbon neutral signals deeper investment in sectors such as electronic vehicles and renewable energy.

If the 2000s saw the last surge of the old China, and the 2010s the rise of new China, the 2020s will be the decade of China 3.0 – an even more deeply digitising economy.

7. A silicon curtain descends

For the past decade, nations have erected barriers to slow the flow of people, trade and even money. Data has been the one exception. According to Ericsson, mobile data traffic in the third quarter of 2021 alone exceeded all the mobile traffic before 2017.

In the US and Europe, it is the regulators who are trying to rein in the tech giants and even the playing fields. Other countries are filtering data and blocking it from crossing borders, creating the “Silicon Curtain”. Data localisation requirements now act as non-tariff barriers to digital services trade and could reduce the efficiency of digital data trade.

Techno-nationalism is on the rise where countries are viewing private-sector technological developments through the lens of national security.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is likely to accelerate the fragmentation of the global economy – to include financial systems, beyond the traded goods system.

8. Strategic investments

We could witness a renewed capital expenditure cycle in several parts of the world to deal with global warming and geopolitical challenges.

The realisation that a net zero world path is not easy will lead to investments to meet the goals of energy security and expanding alternative supplies. For economic resilience, countries will focus on onshoring some productive capacity; insulating supply chains from geopolitical risk; and building inventories of important commodities and goods. The world of just-in-time management may be structurally changing.

There is a need to increase defence spending especially in Europe and substitution of capital for labour could become necessary as faster wage growth will encourage higher labour-replacing investment.

After 75 years of austerity in Germany, the tide may be turning. The pandemic saw Germany accept aggressive fiscal stimulus and debt mutualisation within the EU. Recent EU bonds are a step in the direction to support these investments.

9. Return of the material world

In the 2000s, the world was overinvested in commodities and underinvested in technology. In the 2010s decade that trend reversed. Now a turn towards the commodities is underway.

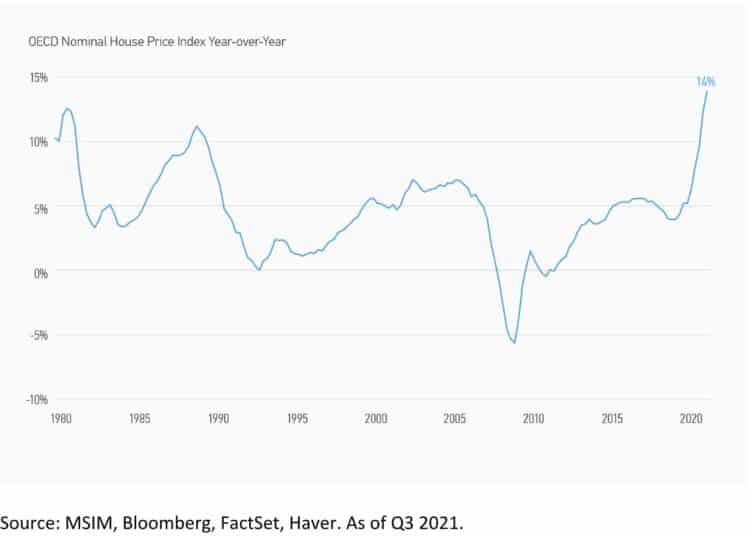

Despite the hype for the intangible economy, the rise in prices in the physical economy – land, cars, raw materials and human labour – tells a different story. A housing deficit has seen home prices rise 14 per cent last year in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, the highest since 1980 (Display 4).

Home prices at their highest year-over-year increase since 1980

Growing demand from millennials helped drive the global boom in both house and car prices in 2021. The cars of the future may be smarter than the current gasoline-burning models, but they also require a lot more copper and aluminium – an electric car requires more than three times as much copper – to connect their batteries and software.

Physical labour shortages are translating into increased wages worldwide. Even the advances in the metaverse have fostered a land-grab as data centres become the new real estate. Behind every digital screen is an array of microchips and costs that have soared amid a global shortage, demonstrating how even the most digital tech sectors are not immune from physical world constraints.

10. Elections, geopolitics and market risk

US midterm elections and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine will likely weigh on global stock markets. The average drawdown in US markets is historically much greater in a mid-term election year compared to any other. The silver lining is that more often than not, markets have bounced back strongly in the year following those elections.

Russia has swiftly achieved pariah status and we believe will remain uninvestable for some time unless there is a regime change, a prospect that will add further uncertainty and global market turmoil.

Our work on 27 geopolitical conflicts since 1939 shows markets have had a probability of being up 70 per cent of the time a year out after the conflict. Disruptive geopolitical events are abruptly discounted by global markets in the short term, while the underlying economic context tends to prevail over the medium to longer term. The commodity price shock as a result of the current geopolitical situation has been significant and, if sustained, could present an altogether different challenge for the global economy, with the potential to affect the monetary policy cycle, growth and earnings cycles.

Panic selling by retail investors who opened trading accounts for the first time during the pandemic could add further pressure. From the United States to Europe, millions of people opened trading accounts for the first time in 2021 and in the US, net purchases of stock topped $1 trillion for the first time, a trend that has continued so far this year.

Economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic has been derailed by geopolitical concerns. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has further advanced trends that were already in play. Food and energy price hikes will add to inflationary pressures as an indebted global economy prepares to tackle climate change and health concerns. Fears of continued conflict in Europe and beyond will increase calls for technology and broader protectionism, bringing a greater appreciation for the physical world. These trends will continue to shape economic, political and market dynamics in 2022 – and beyond.

Jitania Kandhari, deputy CIO of the solutions and multi-asset group, portfolio manager for active international allocation, head of macro and thematic research for the emerging markets equity team, Morgan Stanley Investment Management.