Rolling the clock forward to 2022, this concept could arguably be applied to Australia, not because we are all going hungry, but rather due to the concept of ‘shrinkflation’, which is referring to the reduction in our portion sizes, most notably across the food and beverages industry.

So, what is shrinkflation and is it more than simply a dirty word? To answer this question, it’s first necessary to revisit the concept of inflation and the adverse effects this can have on consumables.

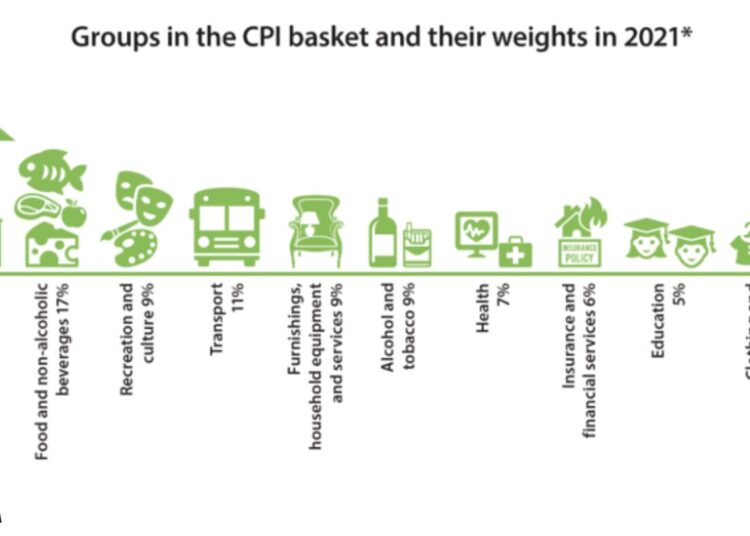

At a high level, inflation refers to the price movement of a pre-defined basket of goods and services, consumed by households (eg. food, beverages, housing, apparel). The most well-known measure of inflation is the consumer price index (CPI), which is also referred to as headline inflation, and this is calculated by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) and released on a quarterly basis. The ABS also produces alternate measures of inflation including trimmed mean and weighted median, with the former commonly referenced as a more representative measure of price movements as it excludes the most variable components, i.e. energy, food.

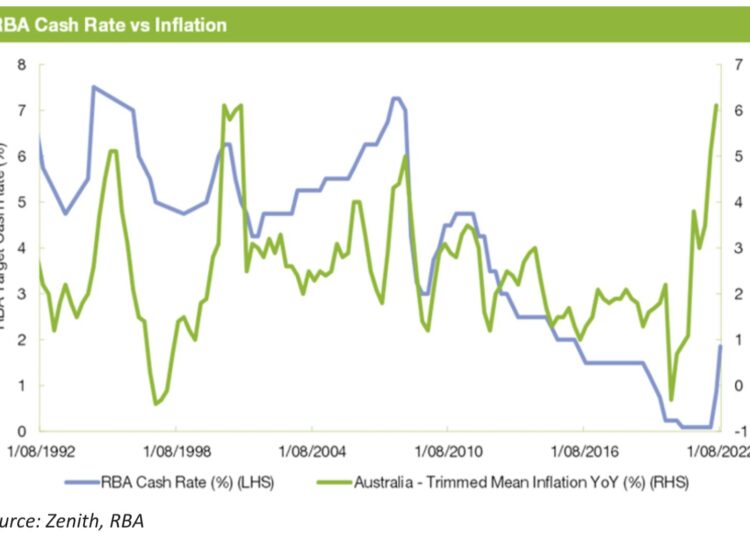

Inflationary pressures can have a significant impact on economic growth as rising prices alter consumption patterns, business investment, government expenditure programs, and ultimately, the trajectory of an economy. Recognising this, the Reserve Bank (RBA) introduced an inflation targeting program in 1993, with the goal of actively managing the domestic inflation rate within a 2 per cent p.a to 3 per cent p.a. band. To achieve this targeted outcome, the RBA has responded to sustained inflationary pressures by increasing interest rates to mitigate the negative effects from rising living costs and an erosion of purchasing power. This response mechanism is demonstrated in the chart below.

What’s causing high inflation?

In its most recent release, the ABS reported that the inflation rate in Australia had reached 6.1 per cent, the fastest annual pace since 2001. Pricing pressures were most evident across food, housing, transport and education, as these industries were impacted by a range of factors including:

-

An increase in raw material prices due to delays across production and distribution channels. This trend has been exacerbated by lockdowns across China, including Shanghai, a global hub for technology production, and home of the largest container port in the world

-

A rise in commodity prices due to the war between Russia and Ukraine, which has been most notable in terms of its impact on energy prices. As a result of sanctions and fears over the free flow of supply, oil prices have risen, translating into higher transportation and energy prices worldwide, and

-

A shortage of skilled workers resulting from reduced immigration rates and limited temporary working visas, negatively impacting many service-orientated industries. While the closure of Australia’s domestic border was an intended policy implemented by State and Federal authorities to curb the transmission of COVID-19, a subsequent relaxation of these restrictions has yet to materially impact the number of people immigrating to Australia. The limited flow of offshore university students and skilled labour has had the greatest impact, contributing to the upward pressure on wages and an unemployment rate that is approaching a 50-year low.

The impact on businesses

Faced with this inflationary backdrop, the natural question is ‘how are corporates responding?’. Well, the answer to this depends on their ability to pass on rising input costs (ie. raw materials, transportation, wages) to the end consumer. In some industries (i.e. those where competition is low and there are few substitutes), it may be feasible to increase the price of consumables in full.

However, in other market segments, this is just not possible and to protect profit margins, corporates have started to consider alternative ways to absorb these costs.

Shrinking on the shelves

One such approach has been to reduce the size of product packaging, or the volume of goods sold at a stated price. This approach to downsizing is referred to as ‘shrinkflation’ and yes, it’s a naughty word.

Consider a situation where the input costs associated with producing a packet of chips rises by 20 per cent. It would be difficult to increase the price of this packet of chips by the same amount, noting the choice consumers have in terms of substitutes (ie. a different brand, savoury biscuits). Instead, it may be easier to pass on a small price rise, and reduce the size of the packet of chips — this is the approach observed with respect to some key Australian product lines shown below.

Determining the extent to which shrinkflation becomes a more mainstream concept will be determined by the speed and trajectory of inflation in Australia, and for that matter, around the world. Many economists are forecasting a higher inflation rate in the months to come, albeit there are varying views on when it will peak and then subsequently fall to a level more consistent with the RBA’s targeted range.

While interest rate increases will go some way to restoring markets to a more normal footing, global supply chain imbalances will also have a significant impact. Accordingly, consumers will either need to adjust their consumption patterns or become more comfortable with smaller serving sizes (and potentially a grumbling tummy)!

Implications for investors

So what does shrinkflation have to do with investment markets? Shrinkflation stems from inflation which in turn has ramifications on the direction of interest rates. With much of the market forecasting higher inflation throughout the remainder of 2022, it’s feasible that interest rate volatility remains high as many seek to project the magnitude and timing of future rate hikes. In such an environment, we believe active fixed interest managers are best positioned to respond. This may be achieved through a variety of strategies including directional interest rate positioning, cross-market, yield-curve strategies, and the harvesting yield through roll and carry.

Andrew Yap, head of multi-asset and Australian fixed income, Zenith Investment Partners