Both the supply of and demand for private capital have increased dramatically since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and neither the pandemic nor the subsequent inflationary shocks appear to have significantly dampened that momentum.

There are four key factors driving the transformation of private capital markets today:

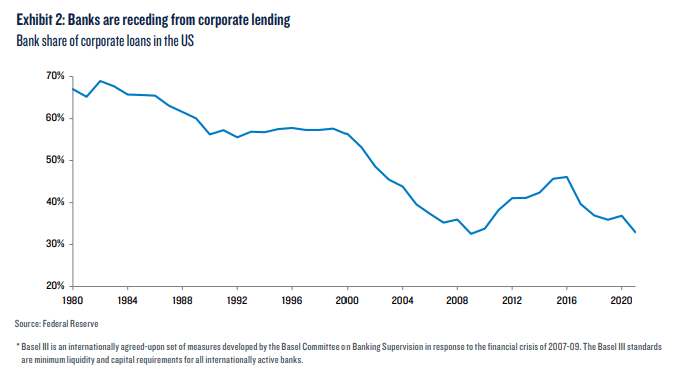

1) Banks and finance companies receding from riskier segments

Commercial banks used to be the primary source of debt financing for firms of all sizes. Over the last 20 years, however, regulatory changes and shifts in business models have led banks to withdraw from certain parts of the market. This will cause banks to narrow their focus to more conservative corporate and real estate lending and ensures a greater role for non-bank lenders going forward.

In addition to the withdrawal of commercial banks, lending from finance companies has dropped sharply. Their activity peaked in the years leading up to the GFC. However, the implosion of securitisation markets triggered by the contagion from subprime mortgages cratered their commercial lending model.

2) Investors seeking income and yield increase allocations to privates

Global institutional investors have significantly increased their exposure to private markets with over 40 per cent saying they expect to further increase allocations in the future. This demand for private assets has been driven by a combination of factors.

First, with ultra-low global interest rates and tremendous compression in corporate bond spreads post-GFC, many investors sought higher-yielding alternatives to corporate fixed-income portfolios — turning to core real estate and mezzanine infrastructure, for example.

Second, many investors prefer the lower frequency at which private markets are marked or repriced. The less frequent pricing has the effect of smoothing valuations for private assets. During periods of market turbulence, this lagged repricing can reduce the swings in net asset values and funding ratios.

Third, the appeal and increasing scale of private markets has also raised interest in broadening individual investor access to private alternatives. The average individual investor has only about 5 per cent of their investable assets allocated to alternatives, and some private credit funds open to individual investors are already approaching $40 billion in size. Future growth could be explosive. Individual investors are estimated to hold about $1 trillion in alternative assets today — which could increase to $4.5 trillion by 2027.

This development has the potential to “democratise” investing by allowing retail investors to access private equity and credit markets that historically have only been available to institutional investors — especially as the investment opportunity set available via public markets alone may be shrinking. However, it is critical that retail investors are educated and can access financial advice on the illiquidity and complexity of private assets versus the transparency and daily liquidity of most publicly listed securities and funds.

3) A growing number of business models may be better suited for private markets

A host of factors has led to the emergence of business models and sectors that may have a comparative advantage in remaining private. Perhaps the most powerful force is the rise of weightless firms. Fueled by the secular shift from manufacturing towards services, companies are moving away from physical capital to a capital-light model centred on investments in intangible assets like R&D, software, intellectual property, data and algorithms.

When scaled, profitable winners in intangible-heavy sectors can ultimately flourish in public markets. However, the journey can often be better appreciated and funded via private markets. This is because intangible-heavy firms typically have a longer path to profitability and are deterred by the drumbeat of quarterly earnings and the whims of impatient public equity markets.

4) Companies are staying private longer

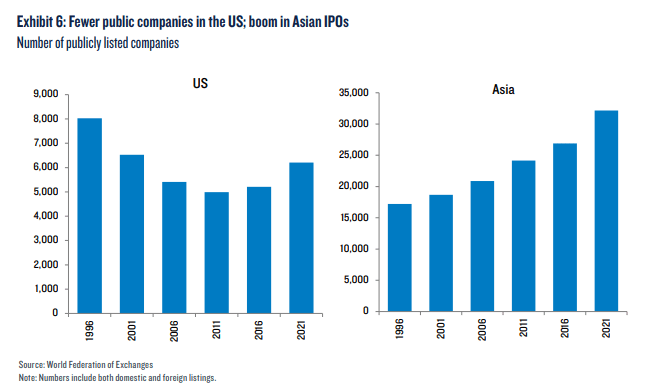

Companies that are going public today do so at a much later stage, the median age of US companies at IPO more than doubled to 11 years over the past decade. This is driven largely by PE-backed companies, which remain in private markets across more stages of their development. Getting a private company to a billion-dollar valuation with VC and other private investments used to be unheard of. Today it has become quite common.

This trend is driven by available capital, and with over $3 trillion in dry powder across private markets, firms will think less about capital and more about strategy when deciding on sources of funding. Asia stands apart in this regard as the number of public market companies has grown quite steadily over the last 15 years, in part because funding alternatives through private capital markets are limited.

How do private capital markets impact systemic risk?

The expanded reach of private capital markets — especially the increasing scale of private credit activity outside the regulated banking system following the GFC — raises important questions about the resulting impact on macroprudential stability and systemic risk across the financial system and economy.

On the one hand, lending activity outside of the regulated banking system has less regular reporting and fewer capital requirements. This makes it harder for regulators and credit market analysts to understand if increasing leverage in the financial system may be unsustainable or create new vulnerabilities. On the other hand, diversifying credit risk beyond a small number of “too big to fail” commercial banks and dispersing it to a broader array of actors potentially reduces systemic risk and broadens access to credit for smaller and more innovative start-ups.

Private credit can also be a nimbler and more stable source of funding compared to commercial bank balance sheets. Investors in these funds, at least historically, have been pension plans and insurers with long-time horizons. Even in the extreme case of economic or financial distress, private creditors can arguably move more swiftly and decisively than large commercial or state-owned banks.

For investors, it is critical to understand two things about systemic risk in private markets. First, today’s private credit funds differ in meaningful ways from the shadow banks of the mid-2000s as they are far less reliant on short-term financing. They appear to have committed sources of capital in closed-end funds to match their illiquid assets so a “run on the fund” is less likely to happen.

Second, although today’s private credit funds may manage some risk better, the underlying credit risk remains, and investors need to distinguish between private credit lenders. Some have demonstrated their ability to navigate economic downturns through multiple credit cycles and have significant experience with workouts, impaired assets and recoveries. By comparison, relatively new entrants to private credit only have experience during a bull market and may be more apt to be swept up in market exuberance.

All in all, these secular trends have shaped private markets over the last 20 years — and at an accelerated pace since the GFC. Though only time will tell how capital markets evolve over the next 20 years as they navigate market cycles and geopolitical upheavals, one thing is clear: private markets will remain a key source of financing for a whole range of innovation and economic activity globally. It is up to investors to have the short-term flexibility and the long-term vision to capture the new opportunities available in deepening and growing private markets while also navigating the unique risks.

Shehriyar Antia, head of thematic research, PGIM