Given enough time, investments are likely to increase in value, even if there are periods of negative returns. By riding out fluctuations, investors can benefit from the general upward trend of the market.

However, not everyone has time to wait for the market to recover from a downturn. Retirees, no longer earning a wage, are drawing down on what they’ve saved. If what they have saved is suddenly worth less during their retirement then it will generate less return, meaning they might have to sell investments at a loss, permanently locking in those losses with less assets to draw on for the future.

This situation has exposed them to what’s known as “sequencing risk”, a problem created when the order and timing of returns clashes with the need to regularly draw monies out of a portfolio. For retirees, Fisher’s assertion works backwards: when you don’t have the luxury of time in the market, timing is (almost) everything.

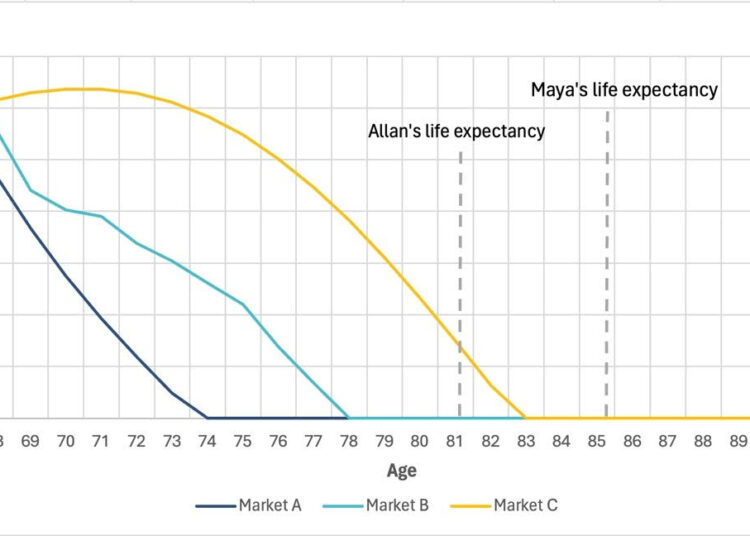

Consider the example of two retirees, Allan and Maya, both starting with the Association of Superannuation Funds of Australia (ASFA) recommended super balance of $595,000 when they retire at 67. They will withdraw $51,630 a year (the ASFA suggestion for a comfortable retirement for a single person).

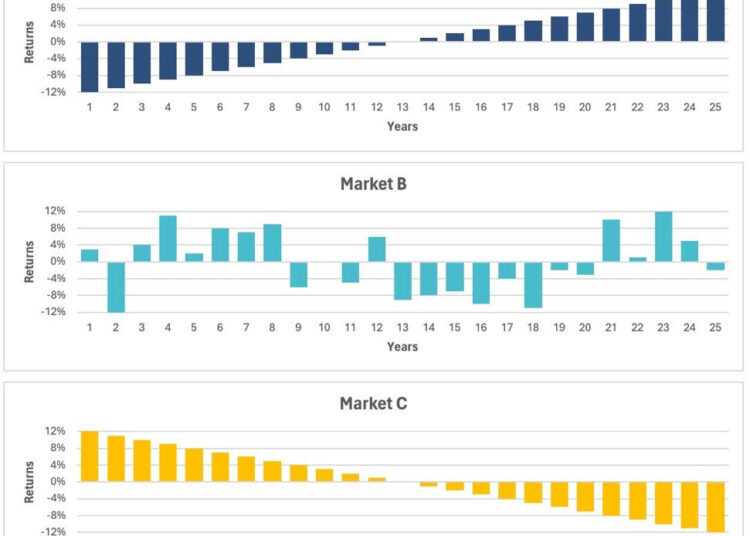

The below charts demonstrate three possible market scenarios, each with a different sequence of annual returns but all with the same average return (0 per cent) over 25 years.

Despite the average return being 0 per cent across all three scenarios, Allan and Maya achieve very different outcomes based on the order of annual returns. In fact, the sequence of returns alone dictated whether the starting balance of $595,000 lasted just seven years or 17 years – highlighting another risk retirees face: longevity risk or the risk that funds put aside for retirement may not see you through to even your average life expectancy.

Getting real

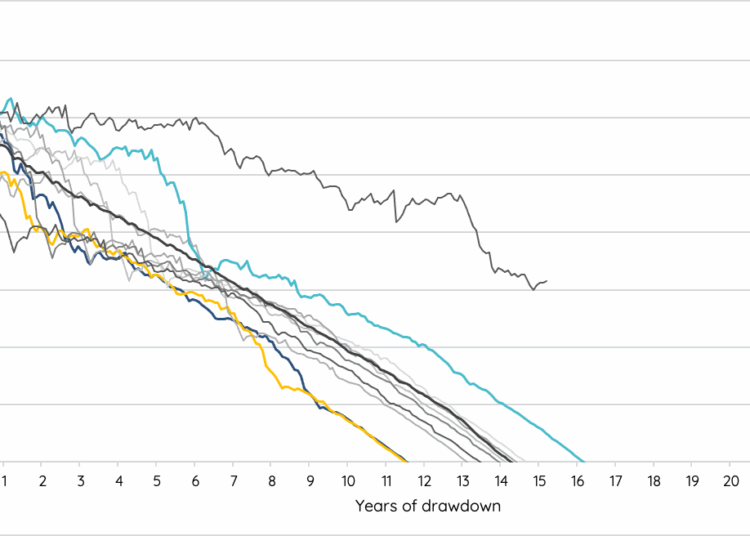

Clearly markets that go up and down in sequential fashion, like examples A and C, are not likely to exist, so let’s look at a period from recent history, the 2000s. If Allan and Maya chose to retire in 2000 (blue line below), by the end of 2009, they would have seen an annualised net return of 1.55 per cent. But that return changes depending on which year during the decade they chose to retire. If Allan retired in 2001 (orange line), his super balance wouldn’t last past year 12, but Maya’s same $595,000 balance would last more than 16 years if she retired just two years later in 2003 (teal line).

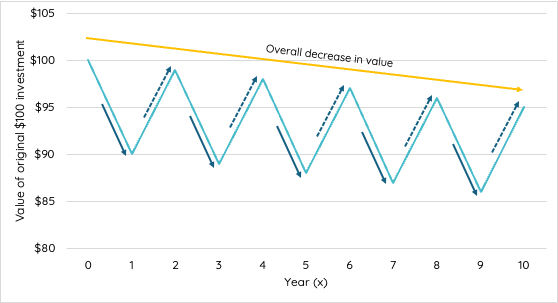

This is due to the volatility of market returns and resulting uneven sequence of returns that either help or hinder the balance of a retiree regularly drawing from their portfolio. While most people understand that market prices can go up and down, the less apparent fact is that once money is lost, it’s much harder to get it back. A loss of 10 per cent actually requires a gain of 11 per cent to break even, likewise 20 per cent down breaks even after 25 per cent up, 30 per cent down needs 43 per cent up and so on.

Knowing this, you can begin to see how withdrawing on losses compounds the effect as your portfolio enters a market upswing with an even lower balance. This is why an actual, money-weighted portfolio return amid market volatility can be much lower than an average of those returns would suggest. The greater the volatility, the greater the gap between the average return over time as reported and the actual return you see in your portfolio.

While the Australian government’s Age Pension provides a basic safety net for retirees, ensuring a modest income even if superannuation savings are depleted, it may not offer the same flexibility and lifestyle options as a well-managed superannuation fund. Effectively managing sequence of return risk can help maintain a wider range of financial choices in retirement, which is crucial given the impact of market volatility on portfolio values.

Take out the guesswork

One possible solution is to just eliminate withdrawals … but that’s not an option for retirees, who would have to “unretire” to accomplish that. It’s also not an option for savings that are held in account-based pensions, as they are structurally required to draw down between 4 per cent and 14 per cent per annum based on age. The other option is to manage market volatility.

While we can’t eliminate volatility, it can be mitigated by investing in more defensive assets. If we look at equities, value stocks fit these criteria best because they are usually well-established companies with stable earnings.

On the other hand, growth equities tend to be more volatile and investors are paying upfront for returns in the more distant future. Finding reliable sources of portfolio income, such as dividends or interest-bearing investments, can also help mitigate the impact of market downturns by providing a steady cash flow to fund drawdowns and creating a buffer to capital losses during market downturns.

At Talaria, we are value investors, yet it is the way we buy the stocks we want to own which makes the biggest impact in reducing portfolio volatility. We sell put options, which is a contract to buy a share at a price lower than the current market price usually two months into the future.

The sale of a put option generates an “option premium” – where the seller (Talaria) is paid a fee. At the time the option matures, one of two things happen: either we take ownership of the stock at or below the agreed price – less the premium or fee which reduces our net entry price and therefore lowers the portfolio volatility. Or if we don’t take ownership of the stock, we still keep the premium which is treated as income for our investors.

Ultimately, if you don’t have time to ride out large downturns in the market, you require a portfolio with significantly less volatility while still generating a regular source of income.

No one can “time” the market, but there are options to help smooth out the ride because the journey really does matter, especially as one doesn’t know when they will arrive at their destination.

Chad Padowitz, co-chief investment officer, Talaria Capital