To add further insult to injury, Margaret Cole, deputy chair of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), warned super funds that they would closely monitor speculative investments into private markets.

Super fund members are entitled to ask difficult questions, such as how and why this investment went so wrong.

First, let’s address the classification of the investment. It has been reported that the investment was a private credit loan; however, it resembles more like a venture capital investment. If it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it is undoubtedly a duck. Despite initially being a debt facility, the debt converted to shares when it could not be repaid. Mark Hargraves, head of international and private equity at AustralianSuper, confirmed, “The combination of deteriorating sales revenue from US corporates due to cost-cutting and the increase in debt service costs due to higher interest rates led to a sharp deterioration in the company’s trading performance, triggering a restructure.”

It’s crucial to accurately label these investments, as they don’t align with the typical characteristics of a private credit investment. This situation highlights the urgent need for transparency in investment language. The lines between what constitutes private credit, equity, or venture capital can often be blurred, especially with US-styled products. This should serve as a cautionary tale, prompting investors to be more diligent in their scrutiny to ensure they’re making informed decisions.

It’s not uncommon for fund managers to use persuasive language and jargon to present certain opportunities as private credit, potentially giving the impression of lower risk. In this case, AustralianSuper was the largest investor and likely understood the level of risk involved. However, had the investment promoter sought funds from a different pool of Australian investors, the potential for a significantly more negative financial impact on investors would have been much higher. This underscores the importance of thorough due diligence in investment decisions and should serve as a stark reminder of the potential consequences of not doing so.

Therefore, investors must understand the true nature of their investments, despite the name and strength of marketing behind the scheme, to make informed decisions.

As a private credit fund manager, I have always had an issue with being lumped together in the so-called “alternative” asset class. However, it has existed in its simplistic form for hundreds of years since the invention of money.

I am not the only one who could be offended; according to the BRW, 13 out of the 100 wealthiest people in Australia have amassed their wealth via property, deemed an alternate asset class with harmful contagions of increased risk.

The industry standards here stem from the 1950s, when the renowned economist Howard Markowitz introduced the Modern Portfolio Theory. This theory stated that a well-diversified portfolio that would outperform relative to other investments needed to consist of 60 per cent shares and 40 per cent bonds, and anything outside these two asset classes would be an alternative by default.

Several other essential questions need to be raised in this context. All stakeholders must be engaged and proactive in seeking clarity and understanding the risks associated with their investments.

It’s essential to differentiate between the various options within private markets. A traditional debt facility, for instance, has a clear goal of repayment of the debt, and in the event of default, a physical asset of greater value than the debt offered as security should be present. This differentiation is crucial for making informed and cautious investment decisions.

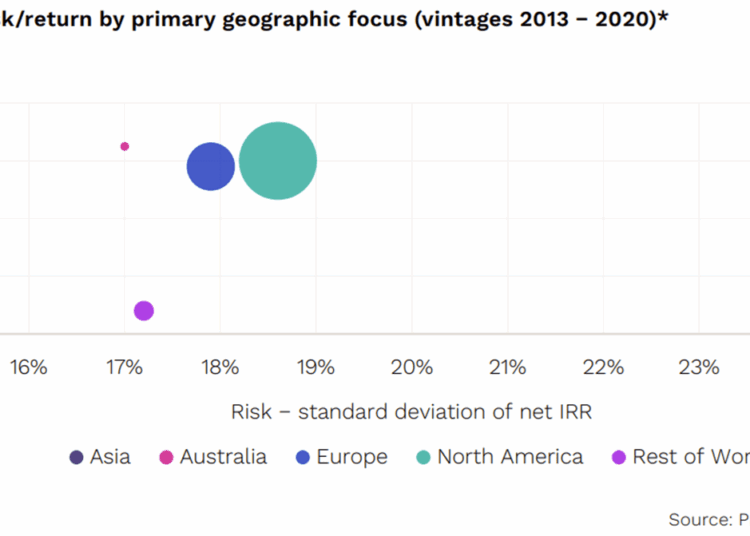

Another question to be asked if the super fund is seeking private credit exposure is whether the US market is a superior place from a risk-reward perspective when countless studies. Data published by Preqin, the leading provider of data on alternatives, demonstrates that Australia is perhaps one of the best value markets in the world due to its strong economy and resilient assets.

While some may say that AustralianSuper’s loss is small in the context of its overall assets under management, this should serve as a cautionary tale for all investors. Private Credit may be very fashionable currently, but it is not a homogenous asset class. Investors need to understand what they are investing in and how they can recover their investment when borrowers default.

Paul Miron, managing director, Msquared Capital