Much has changed in the world economy. Globalisation, “the Washington consensus,” “the end of history” and long supply chains are bygones. Deglobalisation, tariffs, populism, anti-immigration and regional conflict represent the present.

Globalisation accelerated after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, benefiting emerging economies, especially China and India. The expansion of trade, capital, services and labour flows boosted emerging economies from the early 1990s until recent times. For China and India, significant domestic reforms unleashed in the 1980s and 1990s abetted their rapid ascent onto the global stage.

But with globalisation now stumbling, how will the emerging complex fare? Can emerging economies pivot away from goods exports and services outsourcing – activities at risk from deglobalisation? How will they cope with lower levels of foreign investment? Can they find alternative sources of growth and profitability? Will their societies deliver sufficient innovation from within?

In short, can emerging markets (EMs) succeed where success factors must increasingly be homegrown?

For decades, emerging economies have relied on developed economies for access to capital and technology while providing cheap land and labour. Foreign direct investments were incentivised through better returns from cheaper production in EMs, from which goods and services were exported to developed countries. This led to the establishment of long, cheap supply chains from countries such as China to the United States, Europe and Japan.

As tariffs, artificial intelligence and other trade barriers challenge these modes of production and distribution, emerging economies need to pivot. They must reorient trade with one another and rely on domestic drivers for their future growth.

New growth models: domestic demand and “South-South” trade

Fortunately, the export-led model has been a success, leading to rising income and prosperity in emerging economies in China and India, creating opportunities to grow from within.

Global trade flows have already shifted to increased intra-EM commerce, reducing the risks from the US-dominated hub-and-spoke structure of the past. Many emerging economies, led by China and India, have begun to develop stronger, domestic technological capabilities, financial institutions and consumer markets that are accelerating the transition to sustainable domestic growth. We should not forget the importance of domestic reforms playing a vital role too, as we have seen in India, driven by Prime Minister Narendra Modi or in Argentina by President Javier Milei.

Over the remainder of this decade (and beyond), we believe domestic demand is likely to be the strongest driver of economic activity in many emerging economies, and particularly in China and India, both of which boast growing middle-class households with rising purchasing power.

EMs are projected to see their middle-class households double from 350 million in 2024 to nearly 700 million by 2034, with China contributing almost half of that growth. Since 2010, India’s middle-class households have risen from 31 million to over 125 million, while China now has the world’s largest middle class after more than doubling its numbers in the past 15 years.

Those figures are only half the story. Median family income is also rising sharply in China and India and is on par to double every 15 years. Median per capita income in China grew from US$2,500 in 2010 to over US$5,000 last year; and in India, median incomes have also doubled since 2010. This is now the new source of growth.

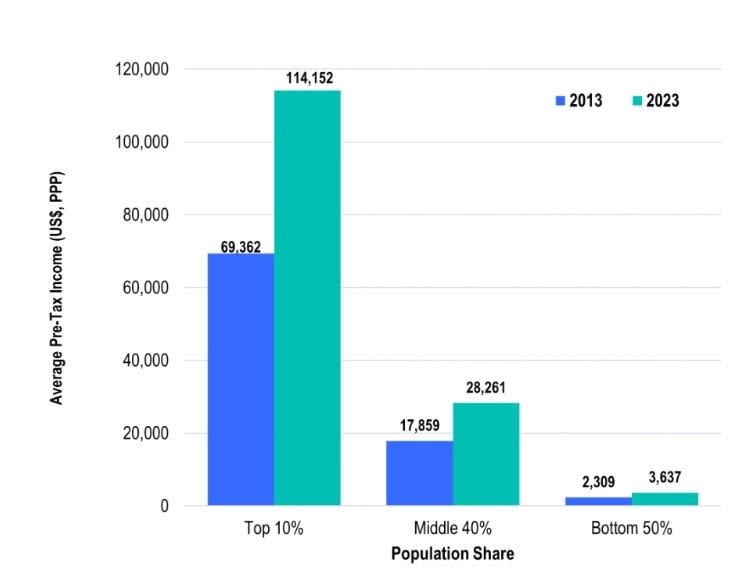

Income and Wealth Distribution - China

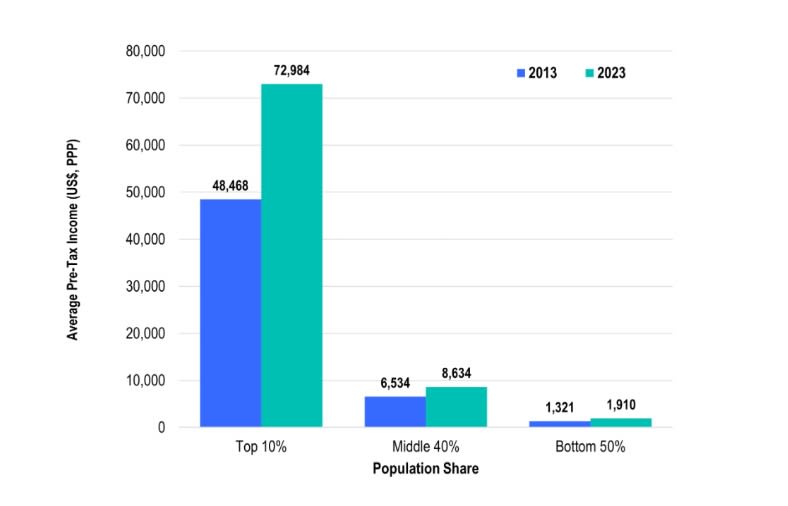

Income and Wealth Distribution - India

Note: India’s middle 40 per cent pre-tax income is just 32 per cent of China’s.

Source: World Inequality Database. Purchasing power parity (PPP) are the rates of currency conversion that equalise the purchasing power of different currencies by eliminating the differences in price levels between countries.

Changes are also underway in terms of global trade flows. A quarter century ago, 80 per cent of exports went to developed economies. According to studies from the Federal Reserve and the World Bank, that share has now fallen to 60 per cent, with 40 per cent of world exports now shipped between emerging economies. As a result, US tariffs and other new import barriers are less damaging today than would have been the case 25 years ago.

Increased intra-EM trade has given rise to more “South-South” dialogue and cooperation. China’s “Belt and Road” initiative, India’s “Act East” policies and BRICS forums are just some of the high-profile ways in which emerging economy collaboration is expanding.

Emerging countries are also making technological progress in areas such as mobile banking (M-Pesa in Kenya), telecommunications (e.g., widely available cell phone service in frontier economies) or biometric services (India). High rates of education, particularly in STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) disciplines, bode well for a world where numeracy, engineering and science sow the seeds of invention.

Michael Browne, global investment strategist, Franklin Templeton Institute