When I was in my early 20s I thought socialism might be the way to go. Two things happened. One I studied economics which led me to the conclusion that socialism/heavy state intervention doesn’t lead to the best outcome in terms of living standards for most. Second, I had the benefit of a trip to the USSR before it and the eastern bloc disintegrated. It must have been Paul McCartney’s faux Beach Boys’, “Back in the USSR” that got me interested! Sure the history and scenery were fantastic and I like the fact that I saw it before the wall came down – but economically it was a mess. And trying to spend excess roubles before we left the USSR was a struggle (nothing but off chocolate to spend them on). “Socialism” seemed to work a bit better in the Deutsche Democratic Republic - but not really and it was a relief to come through Checkpoint Charlie knowing decent food (McDonald’s) was waiting.

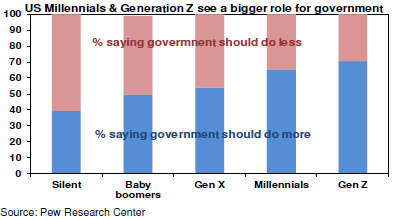

So I ended up gravitating to the centre with the view that the best approach is to allow a market economy with the government providing a good safety net, education and intervening where there are market failures. But a wise man told me when I was young that it’s best to start off on the left when you are young otherwise you will end being like Attila the Hun, as you move to the right as you age. Given the tendency for the young to start off on the left its no surprise to see younger generations favour a bigger role for government in what The Economist magazine has dubbed “Millennial socialism”.

If the Millennials and Generation Z follow the normal pattern, they will shift to the right as they age like their forebears. So nothing new! Well maybe – but there is a big difference now compared to the 1980s. Back in the 1980s the political pendulum (or technically the median voter) was moving to the right. So my ageing was in tune with a big picture political cycle. Now the pendulum is swinging left. We first looked at this three years ago (see “The political pendulum swings to the left”, Oliver’s Insights, June 2016). Since then, it’s become more evident. This note looks at what’s driving it and what it means for investors.

Political cycles beyond elections

Just as the weather, economies and financial markets go in cycles so it is with politics, even beyond standard electoral cycles. This has been clearly evident over the last century:

1930s-1970s - The Great Depression gave rise to a fear of deflation, high unemployment and a scepticism of free markets. The political pendulum swung to the left and culminated in the economic disaster of the high tax, protectionism, growing state intervention and the welfare state of the late 1960s and 1970s that gave rise to stagflation.

1980s-2000s – Stagflation and the failure of heavy government intervention gave rise to popular support for the economic rationalist/right of centre policies of the 1980s. Thatcher, Reagan and Hawke and Keating ushered in a period of deregulation, freer trade, privatisation, lower marginal tax rates, tougher restrictions on access to welfare, measures to reign in budget deficits and other supply side economic reforms designed to boost productivity. The middle class didn’t support higher taxes on the rich because they aspired to be rich. This was all helped along by the collapse of communism and the integration of the old USSR and China into global trade. The political pendulum swung to the right and there was talk of “The End of History” with general agreement that free market democracies were the way to go.

2010 - ? – But post the global financial crisis (GFC) it seems the pendulum is swinging to the left again and support for economic rationalist policies seems to be fading if not reversing.

This reflects a range of factors, in particular:

• The feeling that the GFC indicated financial de-regulation had gone too far;

• Constrained and fragile economic growth in recent years;

• Stagnant real wages and incomes for median households;

• High household debt levels preventing individuals from taking on more debt as a way to boost living standards;

• Rising levels of inequality and perceptions that “it’s unfair”;

• The perceived failure of the baby boomer generation of political leaders to do much about climate change;

• Examples of big business doing the wrong thing;

• A backlash against immigration in some countries; and

• A backlash against globalisation.

Of course, it’s being aided by a dimming of memories of stagflation of the 1970s and its causes and the failures of socialism as highlighted by the USSR (although Venezuela provides a current example). So government-related solutions or socialism seem more attractive. Allied to this are economic theories like Modern Monetary Theory (or rather, Magic Mushroom Theory) that contends that governments can borrow and spend freely in the current environment of spare capacity globally spurred along by the crazy argument that quantitative easing did not cause hyper inflation and higher interest rates so why should bigger budget deficits.

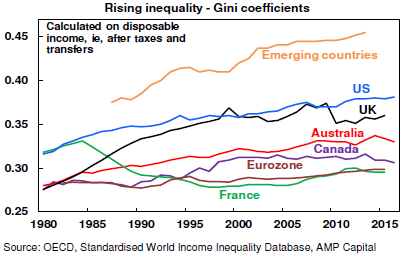

Of these, rising inequality and perceptions of stagnant living standards are the big ones. The next chart shows the Gini coefficient, which is about the best measure of income inequality, calculated on incomes after taxes and transfers. It ranges from zero or perfect equality to one indicating perfect inequality with one household/individual, receiving all income.

The key point is that there has been a general trend higher in inequality during the past 30 years. This is particularly evident in the emerging world but also the US, UK and Australia. Rising levels of income inequality also appears to have come with increase in wealth inequality. Rising inequality may have been more bearable or “masked” in the 1990s and 2000s as nominal income was rising faster and households took on debt to boost their living standards. But in recent times this has become harder and so rising inequality is leading to a backlash.

The political response

In this environment (often populist) politicians have been able to easily tap into voter anger and argue the case for greater public sector involvement in the economy.

• This was evident in support for self-declared socialist Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump in the US in 2016 (although Trump’s focus on deregulation and tax cuts look like a temporary deviation right). It’s now even more evident in the Democrats with the Green New Deal (that plans to rid the US of carbon emissions – and planes and cows – in a decade) and 2020 Democrat presidential aspirants adopting variations of Bernie Sanders’ policies, with proposals for wealth taxes and a 70 per cent tax rate for income above $10 million (which is supported by 59 per cent of Americans). It’s also evident in less US public concern about rising public debt.

• It’s been evident in the Brexit vote in the UK which represented a backlash against globalisation and the left-wing turn in the British Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn.

• In Australia, we are seeing an intensification of the left right divide not seen since 1970s. The ALP is far from the economic rationalist policies of Hawke and Keating. Policies of higher taxes for the “big end of town” (bringing back the Budget Repair Levy and winding back various tax concessions), significantly increased spending on health and education, some reregulation of the labour market and talk of raising the minimum wage to become a “living wage” all suggest a populist focus reflecting a change in voter preferences. The same pressures are also evident in some ways in proposed intervention in the energy sector.

Qualifications

Of course, there are various qualifications to this leftward shift. First, it’s most evident in Anglo-countries because it's here that the swing to the right and economic rationalism was most pronounced in the 1980s and 90s and where inequality is more of an issue. Europe never fully bought into the supply side revolution of Thatcher and Reagan and inequality has not risen much. In fact, France under Macron looks to be embarking on its own version of Thatcherism (with the yellow jacket protests proving nothing more than that Macron is actually doing something) which should augur well for its long-term prospects if Macron stays the course. Second, it’s arguable that if the Democrats are to win the US presidential election next year, they have to win the mid-west – and a socialist presidential candidate may not cut it there. Third, even many on the left are sceptical of ever larger budget deficits – eg in Australia the ALP has been talking of a stronger budgetary position. Finally, there is an argument that a modest move left is necessary to curb the rise in inequality and so save capitalism – much as Keynesian economics “saved” it after the Great Depression.

But what does it all mean for investors?

The risk over time is that a more left leaning electorate will mean a tendency towards bigger government, bigger budget deficits, more regulation, higher effective top marginal tax rates, less globalisation and tougher rules on immigration in some countries. Or it may just mean a stalling in economic reforms. The risk is that it will act as another constraint on productivity and economic growth and eventually see higher inflation if the supply side of the economy suffers.

It’s worth putting this in context. The swing in the political pendulum to the right and the economic rationalist/supply side policies – of deregulation, privatisation, smaller government, tax cuts, low inflation, globalisation – that followed along with the peace dividend from the collapse of communism and attractively high starting point dividend yields and bond yields created a powerful tail wind that drove strong returns in shares and bonds starting in the early 1980s.

Now the environment is very different. Starting point investment yields are ultra-low for most assets and a reversal of economic rationalist policies in favour re-regulation, higher taxes and more government risk slowing productivity growth and eventually resulting in higher inflation.

The key point is that the powerful tailwind from the economic rationalist policies (deregulation, smaller government and globalisation) is now behind us and is contributing along with a range of other factors to a much more constrained return environment for investors. Our medium-term projection for the investment return from a balanced mix of assets have been steadily declining in recent years and is now running around 6.4 per cent pa, which is down from over 10 per cent a decade ago.

In this environment, there is a strong case to focus on investment strategies targeting the achievement over time of goals defined in terms of returns, investment income or whatever is required and using a flexible approach to do so as opposed to relying solely on set and forget strategies that depend heavily on market-based returns. There is also a case to look out for assets that may buck the trend of constrained returns as support for economic rationalist policies recede. French shares may be worth looking at!

Shane Oliver is head of investment strategy and economics and the chief economist of AMP Capital.