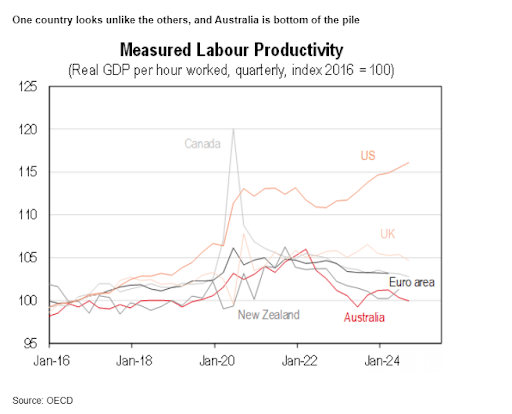

While it’s difficult for one data set to represent a year of economic volatility, HSBC’s Paul Bloxham says that a key story for the Australian economy has been its weak productivity performance.

HSBC has noted throughout the year that productivity could be a reason the Reserve Bank opts not to cut rates in 2024, despite most other developed market central banks doing so.

“Although demand has slowed, weak productivity has constrained the supply-side of the economy, contributing to sticky inflation,” Bloxham said.

The economist said that key questions for 2025 will be why productivity has been so weak, what it means, and importantly, how to fix it.

Not only has measured labour productivity fallen, Bloxham underscored, a longer-term perspective indicates that it is no higher now than it was in 2016.

“As is well understood, lifting productivity is the main way that most countries lift national incomes and living standards. As it turns out, there is another way to do this – that is, to sell what you produce for an ever-increasing price – and this other way is what Australia has done for much of the first two decades of this century.”

During this period, he explained, Australia has benefited from a substantial rise in its terms of trade, coupled with a boost to iron ore, glass, and coal production on the back of the mining investment boom around the turn of the century.

But the economist pointed out that mining investment is now much lower than it was back then, with prices for these products having slumped from their peaks.

“A focus on productivity is needed if Australia is to continue to lift its living standards meaningfully,” Bloxham said, noting that key opportunities are likely within renewables, the green transition and education exports with a keen focus on trading with Asia.

While many other countries are encountering similar productivity challenges, the US has been an outlier. The bank suspects that the US’ stronger productivity growth has played a key role in its soft landing.

“In short, demand has not needed to weaken much to get inflation to fall because the supply-side of the economy has improved substantially, partly because productivity growth has been strong.

“We have argued that part of the explanation for the divergence in the recent cyclical productivity performance across these countries could reflect the design of the pandemic policy response,” Bloxham said.

Namely, most Western countries “deep freeze” policy measures though the pandemic offered greater protection for economies, but likely limited business dynamism.

On the other side of the coin, the US had a hard recession through the pandemic but is also seeing the typical cyclical pick-up in productivity that comes after a hard recession, following significant jobs market and business sector churn.

Expounding on this, Bloxham said that Australia is operating on the other side of this spectrum.

“Productivity has been weak and with growth in demand slowing, but not declining – as has been seen in other countries like New Zealand, the UK and some European economies – Australian inflation has been sticky and elevated.

“Australia needs productivity to pick-up not just to improve living standards but also to help disinflate and allow the RBA to cut rates.”

Looking ahead, he believes that a “broad-based” policy approach is needed.

“This should include a focus on tax reform, competition policy, deregulation and improving the availability of skill workers.

“As Australia heads towards a federal election in 2025 (by 17 May at the latest), how to lift productivity ought to be a key focus,” Bloxham said.