Speaking in Sydney yesterday, JP Morgan Asset Management global head of multi-asset strategy John Bilton indicated that the productivity levels of the global work force were dipping due to an ageing population.

“It’s not the population is shrinking, it’s the working age population growth [that] is declining,” Mr Bilton said.

“So the question is: where can that labour come from?”

Presenting findings from JP Morgan’s latest Long-Term Capital Market Assumptions whitepaper, Mr Bilton said certain emerging technologies would step in to fill that gap.

“What we would probably see is that automation can be a substitute for labour and that’s particularly where there is a shortage of labour,” he said.

“So [in] countries like Japan, places in Europe where we’ve got some shortfalls, we would expect to see technology increasingly bought in as potential substitute to make up that gap.”

However, he stressed that for investors, this did not mean “pure-play technology firms” or “picking one stock versus another”.

“It’s about where we’re seeing applicable technology, which could boost earnings or returns across the industry generally,” he said.

He pointed to cloud computing, the Internet of Things, artificial intelligence, robotics and blockchain technology as areas that could “affect large blocks of the equity market today”.

“We would be looking for companies in sectors which are at cutting edge of deploying this kind of technology,” he said.

“I’m not a stock-specific guy.

“But it’s more a question of: if you are seeing these types of technologies being invested in and successfully deployed within business models, to our mind, these are things which are not just ‘dotcom-era’ ideas.

“These are more real labour saving or cost saving technologies that potentially could see positive returns for companies and sectors deploying this actively.”

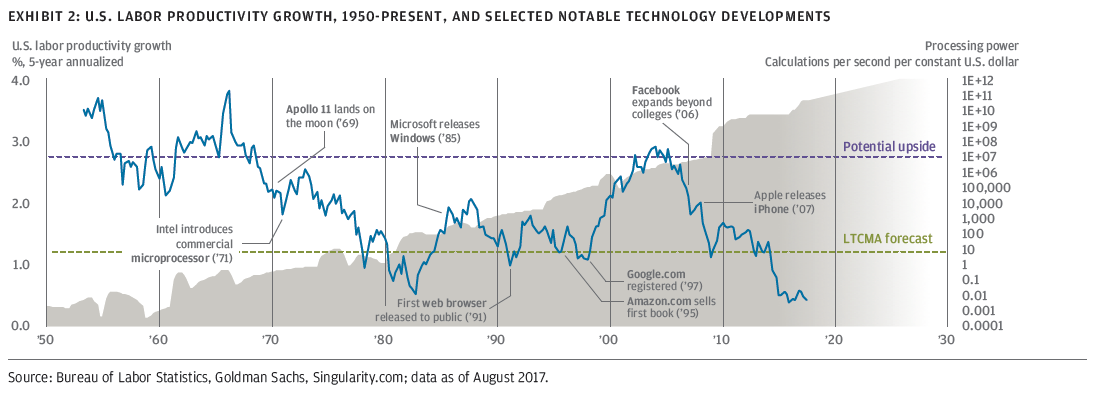

According to the whitepaper, productivity growth following the introduction of new technologies had come in “fits and starts, often but not always coinciding with the widespread adoption of specific previous breakthroughs”, some of which had “greater impacts on productivity than others”.

Making reference to the chart, Mr Bilton pointed to the volatile nature of productivity growth.

“We believe strongly that technology investment will drive productivity gains, but it’s not necessarily predictable exactly when that will happen,” he said.

For example, in the early 1970s microprocessors were introduced, but productivity fell in the ensuing decade.

“It wasn’t really until, in the 1980s, we began to get the socialisation of computing,” Mr Bilton said.

“You saw this gradual upsurge, then real surge in productivity that we saw during the early 2000s.”

If a “proper surge” in technology were to occur, Mr Bilton predicted “another per cent or percentage and a half” rise in productivity.

“Whether we get that depends on the adoption rates of technology, depends a lot in terms of how policy is set to use technology and to deploy across industry, but it gives us an upside risk,” he said.

“Technology to us is an upside risk.”